Friday, December 23, 2005

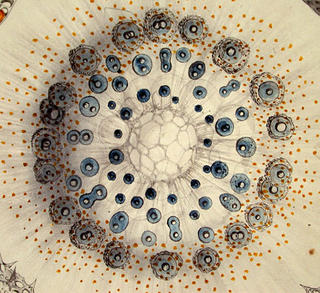

B. Jones Archive: The Vision of God Laughing

B. Jones' notes indicate that the initial inspiration for this design was the "triadic (fourth implied) image" of Shiva Maheshvara at the Elephanta Caves in India.

However, the final design, he once told me, was a "blatant rip-off" of an 18th century silk embroidery of Avalokitesvara. I believe he saw this in New York. Of course I do not have access to that, but I did find this image from blotterart.net:

The story was that Avalokitesvara vowed to save all sentient beings. Right when he thought he had completed his task, he found that there were still some unsaved beings. For an instant, he doubted his ability to fulfill his vow and his head shattered into a myriad of faces. However, the god to whom he had made the vow blessed him again and made him even more powerful, with all of the faces able to look in all directions, able to discern all unsaved beings and thus forever liberating Avalokitesvara from doubt.

Concerning the title, Jones told me that he first came across it in Kundera, but that it is an old Jewish idea: "What man calls thinking, God calls laughter". We had many discussions about this and there is much more to say in a later post.

B. Jones never posted any of his drawings here. I once asked him about this and he replied that he didn't see that they would be of much use to others, that they were like mirrors that only he could see into. I disagreed then and I disagree now.

Thursday, December 22, 2005

B. Jones Archive Project: Stamp Detournements

WEIRD DANCING IN ALL-NIGHT computer-banking lobbies. Unauthorized pyrotechnic displays. Land-art, earth-works as bizarre alien artifacts strewn in State Parks. Burglarize houses but instead of stealing, leave Poetic-Terrorist objects. Kidnap someone & make them happy. Pick someone at random & convince them they're the heir to an enormous, useless & amazing fortune--say 5000 square miles of Antarctica, or an aging circus elephant, or an orphanage in Bombay, or a collection of alchemical mss. Later they will come to realize that for a few moments they believed in something extraordinary, & will perhaps be driven as a result to seek out some more intense mode of existence.

- Slightly larger images on the click -

Thursday, December 15, 2005

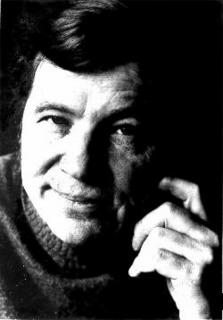

R.I.P. - Charles "Bonesy" Jones

On the 15th of November of this year, my good friend and mentor, Charles "Bonesy" Jones passed away. He was 60 years old.

On the 15th of November of this year, my good friend and mentor, Charles "Bonesy" Jones passed away. He was 60 years old.Just after the first of the year, while riding his bike at night, he was evidently struck by a car. No one is quite sure what happened. Mr. Jones had no memory of the event itself and even suggested that perhaps he had just fallen off his bike - over and over. (He referenced this, in his typically cryptic way, in his post from January 27th.)

However his injuries were fairly severe for a man his age: a major concussion and a badly separated shoulder. Initially this was thought to be the extent of it. But as the weeks passed and the wounds and shoulder healed, it became obvious that he was also suffering from some cognitive problems. Problems with memory and a progressive aphasia that further deteriorated into feverish dementias. His health declined rapidly over the summer. By October, it was clear to him that he did not have much longer to live.

He always hated doctors and hospitals and had no desire to spend his last days surrounded by either. He asked me if I would assist him in making "one last pilgrimage to the Desert". Of course, I agreed.

He died beside the fire on the cold but clear night of November 15th in the hills above the Chama River in New Mexico, not far from his beloved Monastery. His last words were: "In the end: bones..." - as fitting an epitaph, at least to my mind, as any Japanese Death poem.

I knew Mr. Jones for almost 20 years. No one has had a greater influence upon my life. As much as he prepared me over the years for "the day the bones step out of the skin", it still shocks and saddens me in every hour to realize that he is no more. The absence of his burning presence will haunt me for the rest of my days.

So I come to why I am writing this on his weblog: Mr. Jones graciously left me all of his, resolutely few, worldly possessions, including this computer and his extensive library. There are trunks full of writings, drawings, music and the mysterious ephemera of a rich and strange life. I have not been able to even look at it until just recently.

In an attempt to make some order out of it all, I turned this computer on the other day and began to organize his files. Amongst the labyrinthian folders inside folders, I stumbled upon one for this weblog and a series of notes and images that I imagine he intended someday to post. I remember him mentioning to me more than once how much he enjoyed his "occasional ranting and occluded confessions" related to The Laughing Bone.

It struck me that it might also be a good medium for me to exercise and exorcise a few of my own daemons. Additionally, I hope to publish selected fragments of interest from Mr. Jones. In this way, perhaps I can work through some portion of the grief and loss that seems to never diminish but only increase with each day I wake up to where he is no longer.

Sincerely,

Scot Casey

Friday, September 16, 2005

Though mounted in that saddle Homer rode

Recently I was sent notice that the eminent translator, Stanley Lombardo, was going to perform selections from his work at the University of Texas in Austin. I shall certainly take the always perilous journey from Little Hope to Austin to attend. Several years ago, a good friend who had just completed a course of study in ancient Greek, excitedly pushed a copy of Lombardo's translation of the Iliad into my hands. "There is no such thing as translation, only rendering," he told me. "And this is the best rendering of Homer so far."

I was immediately struck by the cover photograph, "Into the Jaws of Death", 6 June 1944, of the Marines landing on the beaches of Normandy. I turned to the Translator's Preface and read:

A musician once asked Ezra Pound if there was anywhere one could get all of poetry, in the sense that one could get all of music in Bach. Pound's response was that if a person would take the trouble to really learn Greek, he could get all of it, or nearly all of it, in Homer. If Pound is right, and I think he is, then the real work of the Homeric translator is clear: to produce a version that is responsive not only to meaning and nuance but also to overall poetic effect, a version that has as much poetry as the original text, the translator's talent, and the current literary situation will yield. This requires loyalty to the essential qualities of Homeric poetry - its directness, immediacy, and effortless musicality - more than replication of the verse's technical features (although these must at least be suggested). In the end, it is the greatness and reach of Homer as a poet that the translator must confront. Accuracy and nuance are attainable through scholarship and good writing; technical problems admit various solutions; but what we love is the poet's voice, and finding its tone, rhythm, and power is the heart of Homeric translation.Lombardo's "rendering" was, as you might imagine from those prefatory remarks, excellent. I had read Robert Fagles translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey not long before and found Lombardo's to be much more immediate - in the sense that, even with its near colloquial modernity, it felt closer to Homer; rather, who I imagined Homer to be.

Down there at the roots of the Western Canon is such a strange beast.

In his essay, Homer in English, George Steiner writes:

To borrow an image from plant genetics: the sequence of translations from Homer provides a unique radioactive tracer. By its luminescent progress, we can follow the development of the language, of its vocabularies, syntax and semantic resources, from root to stem, from its stem to its multiple branches and leaves. Every model of English lexical and grammatical observance is visible in this chain: all the way from the most ornate and experimental, as in Chapman or Joyce, to the 'basic English' purpose in I. A. Richards's narration of the fury of Achilles.....Which brings Christopher Logue's translations (accountings) to the front and center. In the author's note to War Music: An Account of Books 1-4 and 16-19 of Homer's Iliad, he states:

This vivacity if structural illumination, of dynamic legibility, as in a radioactive tracer coursing through organic tissue, springs from the nature of translation itself. For it is through the process of translation that language is made eminently self-aware. Translation constrains it to formal and diachronic introspection, to an explicit investment and enlargement of its historical, colloquial and metaphorical instruments. Simultaneously, translation puts language under the pressure of its limitation. It will solicit modes of perception and designation which that language had left underdeveloped, or had altogether discarded. An act of translation draws up the balance-sheet, as it were, for the target language.

Rather than a translation in the accepted sense of the word, I was writing what I hoped would turn out to be a poem in English dependent upon whatever, through reading and through conversation, I could guess about a small part of the Iliad, a poem whose composition is reckoned to have preceded the beginnings of our own written language by fifteen centuries.Logue's translation is, as Steiner remarks, incandescent. White-hot flashing neon that is not always the best modality for expressing a "loyalty to the essential qualities of Homeric poetry": but still illuminating. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Logue's "balance-sheet" for the language opened up aspects of the inner drama of the text that I had never quite caught before. The immediacy here wasn't so much one of getting close to Homer as it was one of getting close to the core humanity of the poem.

My reading on the subject of translation had produced at least one important opinion: "We must try its effect as an English poem," Boswell reports Johnson as saying; "that is way to judge of the merit of a translation."

A few comparisons between the Lombardo and Logue translations:

Rage:A while back. Jim Lewis profiled Christopher Logue in Slate on the occasion of the publication of All Day Permanent Red: An Account of the First Battle Scenes of Homer's Iliad. Is is an informative and amusing piece. I particularly enjoyed this passage (the line, "a man whose eccentricities border on madness", is perfect):

Sing, Goddess, Achilles' rage.

Black and murderous, that cost the Greeks

Incalcuable pain, pitched countless souls

Of heroes into Hades' dark,

And left their bodies to rot as feasts

For dogs and birds, as Zeus' will was done.

- Lombardo, Book 1, 1-7

Picture the east Aegean sea by night,

And on a beach aslant its shimmering

Upwards of 50,000 men

Asleep like spoons beside their lethal fleet.

- Logue, Book 1, 1-4

"This time we will save you, mighty Achilles,

This time- but your hour is near. We

Are not to blame, but a great god and a strong Fate.

Nor was it slowness or slackness on our part

That allowed the Trojans to despoil Patroclus.

No, the best of gods, fair-haired Leto's son,

Killed him in the front lines and gave Hector the glory.

As for us, we could outrun the West Wind,

Which men say is the swiftest, but it is your destiny

To be overpowered by a mortal and a god.

Xanthus said this; then the Furies stopped his voice

And Achilles, greatly troubled, answered him:

"I don't need you to prophesy my death,

Xanthus. I know in my bones I will die here

Far from my father and mother. Still, I won't stop

Until I have made the Trojans sick of war."

And with a cry he drove his horse to the front.

- Lombardo, Book 19, 149-154

And as it ran the white horse turned its tall face back

And said:

"Prince,

This time we will, this time we can, but this time cannot last.

And when we leave you, not for dead, but dead,

God will not call us negligent as you have done."

And Achilles, shaken, says:

"I know I will not make old bones."

And laid his scourge against their racing flanks.

Someone has left a spear stuck in the sand.

- Logue, Book 19, Pax

Certainly, Logue's resume is piebald, at best. Among other things, he wrote the screenplay for Ken Russell's Savage Messiah, a biopic about the French sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska; he is credited as playing the role of the "spaghetti-eating fanatic" in Terry Gilliam's Jabberwocky, and as recently as 2001, he had a bit part in The Affair of the Necklace, a historical drama starring Hilary Swank. Moreover, the flap copy on All Day Permanent Red (whose title comes from a Revlon lipstick ad) mentions the availability of a seven-CD set of Logue's work titled Audiologue, which on closer inspection proves to include 500 minutes of readings, some of them set in the late 1950s to jazz. For better or worse, this is not the sort of activity that helps establish someone as a Major Poet, and you might be excused for dismissing Logue as a dilettante - or, at least, a man whose eccentricities border on madness.I'll leave the last words to Stephane Mallarme:

And yet.... He is an extraordinary writer, the books are brilliant, his poetry strong, witty, and intelligent. He is not a charlatan: not at all. To be sure, his Iliad rings in a different key than most contemporary poetry, which often seems dominated by, on the one hand, obscure and inward-looking lyrics, and on the other, by the self-indulgent, tin-eared efforts that emerge from poetry slams. Logue is something else; narrative and frank, but his Homer is as alive as any more modish author.

We were the last romantics -- chose for theme

Traditional sanctity and loveliness;

Whatever's written in what poets name

The book of the people; whatever most can bless

The mind of man or elevate a rhyme;

But all is changed, that high horse riderless,

Though mounted in that saddle Homer rode

Where the swan drifts upon a darkening flood.

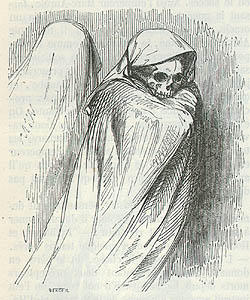

Hell mouth, as figured in the Roxburghe Ballads.

Hell mouth, as figured in the Roxburghe Ballads.University of Victoria Library.

1.

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!

"Charge for the guns!" he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

2.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!"

Was there a man dismay'd?

Not tho' the soldier knew

Someone had blunder'd:

Their's not to make reply,

Their's not to reason why,

Their's but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

3.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

4.

Flash'd all their sabres bare,

Flash'd as they turn'd in air,

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wonder'd:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro' the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reel'd from the sabre stroke

Shatter'd and sunder'd.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

5.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro' the jaws of Death

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

6.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honor the charge they made,

Honor the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred.

Monday, September 05, 2005

3 Vectors of The Magical Negro

From Strange Horizons: Stephen King's Super-Duper Magical Negroes By Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu

[R]ecently, in 2001, during a discussion with students at Washington State University, film director Spike Lee popularized the concept by renaming it the "Super-Duper Magical Negro." He was referring specifically to John Coffey (played by Michael Clarke Duncan) in The Green Mile and Bagger (played by Will Smith) in The Legend of Bagger Vance.

Both films are about a white man whose moral and emotional growth is made possible by the appearance of an almost angelic mystical black man. In The Green Mile, Coffey eventually dies after effecting great change on the white protagonist and just about everyone else around him. In The Legend of Bagger Vance, Bagger (whom the author of the book said was based on the Hindu deity Bhagavan Krishna) leaves as mysteriously as he arrived, once Rannulph Junuh's life is back on track. Both characters, John Coffey and Bagger, are only important in relation to the protagonist of each story.

Black KrishnaInterestingly enough, Krishna means "black" in Sanskrit. The name is often translated as "the black one," and early pictorial representations generally showed him as dark- or black-skinned. By the nineteenth century, he had become the blue-skinned deity most are familiar with.

Here are what I call the Five Points of the Magical Negro; the five most common attributes:

- He or she is a person of color, typically black, often Native American, in a story about predominantly white characters.

- He or she seems to have nothing better to do than help the white protagonist, who is often a stranger to the Magical Negro at first.

- He or she disappears, dies, or sacrifices something of great value after or while helping the white protagonist.

- He or she is uneducated, mentally handicapped, at a low position in life, or all of the above.

- He or she is wise, patient, and spiritually in touch. Closer to the earth, one might say. He or she often literally has magical powers.

From Wikipedia:

The "Magical Negro" (sometimes called the "Mystical Negro" or "Magic Negro"), according to some critics and commentators, is a stock character who appears in some films, books, and television programs. The term has been in use since at least the 1950s, but has since been popularized by Spike Lee, who dismissed the archetype of the "super-duper magical negro" while discussing his 2000 film, Bamboozled. The word "negro" in the phrase, despite being now considered offensive, is used intentionally for that very reason by many critics, to emphasize their belief that the archetype is a racist throwback to a less enlightened time.

When he first encounters the (invariably white) protagonist, the Magical Negro often appears as someone uneducated and in a low station of life, such as a janitor or prisoner. The black character is depicted as wiser and spiritually deeper than the protagonist, and the purpose of the "Magical Negro" in the plot is often to help the protagonist get out of trouble, and to help the white character recognize his own faults and overcome them. The black character may literally have special powers, or he may be mysterious in a way that suggests otherworldliness.Although it is usually a well-meaning attempt to portray a positive black character, critics like Lee, Ariel Dorfman, and Aaron McGruder believe that the use of this stock character is racist, because it perpetuates the idea that blacks should be subordinate to whites. The racial roles of the archetype are rarely reversed (lower-class white character helps a troubled black character).Song of the South, 1946

Because of its unrealistic depiction of the post-Civil War "Reconstruction" era,

this film has been quietly retired by the Walt Disney Company in the USA since 1986 (40th Anniversary re-release).

The Magical Negro can be considered a form of the "noble savage" or "wise old man" archetype. Variants include the Native American who helps pragmatic whites discover their inner spirituality and brings them back in touch with nature, and the servant (of any non-white race) who sacrifices himself to save his master.

Alleged examples of "Magical Negroes" include:

- Alexander Levine in Bernard Malamud's short story The Angel Levine

- Noah Cullen (Sidney Poitier) in the film The Defiant Ones (1958)

- Dick Haloran (Scatman Crothers) in the Stephen King novel The Shining (1977), later a 1980 film

- Willie Brown (Joe Seneca) in the film Crossroads (1986)

- John Coffey (Michael Clarke Duncan) in the serialized Stephen King novel The Green Mile (1996), later a 1999 film

- Albert Lewis (Cuba Gooding, Jr.) in the film What Dreams May Come (1998)

- Cash (Don Cheadle) in the film The Family Man (2000)

- Bagger Vance (Will Smith) in the film The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000)

- An angel (Gabriel Casseus) in Bedazzled (2000)

- God (Morgan Freeman) in the film Bruce Almighty (2003)

- The blind handcar-pumper (Lee Weaver) in the film O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000)

- The old woman seer in the Stephen King novel The Stand

- The barkeeper Guinan in Star Trek: The Next Generation

- The Oracle in The Matrix Reloaded

- Gabriel (voice of Delroy Lindo) in The Simpsons episode "Brawl in the Family" (DABF01, 2002) (a deliberate parody of the archetype)

Note that black characters with apparent supernatural powers who are portrayed as independent, have a power level roughly equal to that of the others and are not subservient to whites, such as Star Wars' Mace Windu, Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) in the film The Matrix (1999) and Storm in X-Men are not usually considered "Magical Negroes", nor are helpful non-white characters without some magical or fantastical element.

From Uncle Remus and His Sayings by Joel Chandler Harris, Edited with an Introduction by Robert Hemenway:

"Harris was obviously of two minds about his fame – on the one hand he sought it by continuing to write, on the other he felt unworthy of it – and those two minds were seldom very far from the surface. In an extraordinary letter to his daughter, well after he was a national figure, Harris personified the two sided of his personality:"

(Thanks to Matt and Keri for the conversation.)

As for myself - though you could hardly call me a real, sure author- I never have anything but the vaguest ideas of what I am going to write; but when I take my pen in hand, the rust clears away and the “other fellow” takes charge. You know all of us have two entities or personalities. That is the reason you see and hear persons “talking to themselves.” They are talking to the “other fellow.” I have often asked my “other fellow” where he gets all his information, and how he can remember, in the nick of time, things that I have forgotten long ago but he never satisfies my curiosity. He is simply a spectator of my folly until I seize a pen, and then he comes forward and takes charge.

Sometimes I laugh heartily at what he writes… it is not my writing at all; it is my “other fellow” doing the work and I am getting all the credit for it. Now, I’ll admit that I write the editorials for the paper. The “other fellow” has nothing to do with them, and, so far as I am able to get his views on the subject, he regards them with scorn and contempt… He is a creature hard to understand, but, so far as I understand him, he’s a very sour, surly fellow until I give him an opportunity to guide my pen in subjects congenial to him; whereas, I am, as you know, jolly, good-natured and entirely harmless.

Now, my "other fellow," I am convinced, would do some damage if I didn’t give him an opportunity to work off his energy in the way he delights.

Thursday, September 01, 2005

Backwater Blues

Backwater Blues by Bessie SmithWhen it rained five days and the skies turned dark as night

When it rained five days and the skies turned dark as night

There was trouble taking place in the lowlands at night

I woke up this morning, wouldn't even get out of my door

I woke up this morning, wouldn't even get out of my door

Enough trouble to make poor girl wonder where she gonna go

They rowed a little boat, about five miles 'cross the farm

They rowed a little boat, about five miles 'cross the farm

I packed up all my clothing, throwed it in and they rowed me along

It thundered and it lightened and the winds began to blow

It thundered and it lightened and the winds began to blow

There was a thousand women, didn't have no place to go

I went out to the lonesome, high old lonesome hill

I went out to the lonesome, high old lonesome hill

I looked won on the old house, where I used to live

Backwater blues have caused me to pack up my things and go

Backwater blues have caused me to pack up my things and go

'Cause my house fell down and I can't live there no more

Hmm, I can't live there no more

Hmm, I can't live there no more

And there ain't no place for a poor old girl to go

***

Note: This was one of her most successful records; it was recorded just before the catastrophic great Mississippi flood of 1927.

Note: backwater, mostly old river beds which are left to take the excess flood water to relieve pressure on the levees (embankments). As the height of the water is excessive, however, breaches in the levee walls are deliberately made at certain points to allow particular areas to flood and thus lessen the pressure of water. These are the "backwaters," which occur in the St. Francis Basin to the west of the river between Memphis and Helena, in the great Yazoo-Mississippi Delta north of Vicksburg, in the Tensas Basin west of Natchez, and at other selected points.

Original reference via Apophenia (may you find all your friends).

Lyrics and notes via Blues Lyrics.

Tuesday, August 23, 2005

Colin Wilson: The Odyssey of a Dogged Optimist by Robert Meadley

Received an email this morning that absolutely made my day. (Thank you, L. Evans from the British Library.) It pointed me to a page for Savoy Books where you can download for FREE a pdf (2.3 mb) of Robert Meadley's defense of Colin Wilson, The Odyssey of a Dogged Optimist. Haven't had a chance to read it yet. But here is some description from the site:

Robert Meadley's second book for Savoy (after A Tea Dance at Savoy) is a funny, clever and erudite defence of Colin Wilson following a series of splenetic reviews of Wilson's biography, Dreaming To Some Purpose, in The Observer and elsewhere. Lynn Barber, Adam Mars-Jones and Humphrey Carpenter were among those using publication of Wilson's autobiography—and large quantities of broadsheet space—to attempt a wider demolition on his life and career. Meadley recognises that in these situations attack is the best form of defence and gives no quarter, assassinating each of the egregious hacks in turn, as he also examines the qualities that make Wilson's work so insightful and compelling.

Monday, August 22, 2005

Ernst Haeckel: Evolution's controversial artist

Laurie Lipton: Drawings

Laurie Lipton

66 X 96.5 cm - charcoal and pencil on paper

Be sure to scroll down through the stunning catalogue or you will miss gems such as this:

Laurie Lipton

51 X 59 cm - pencil on paper

(via the WOW report)

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Colin Wilson: Slight Return

One of the authors that I used to seriously collect was Colin Wilson. At one point in my life, his books - especially the Outsider Series - were like maps, guiding me through unknown territories. I eagerly hunted down everything in and out of print. And in those dark pre-Amazon days, it was a real triumph of discovery to find a copy of the long out-of-print Beyond the Outsider, signed by Wilson, on the dusty lower shelf in an old bookstore.

I am still a great fan of his work. I will admit that his prolific ventures through the fields of the occult and crime have left me somewhat cold. But I retain a great fondness for his earlier "philosophical" books and fiction. Consequently, I was a bit dismayed, slightly amused, to read the recent round of reviews for his latest book, the autobiography, Dreaming to Some Purpose. In particular, the non-review by Lynn Barber in The Guardian made me wince with its winking venom, reminding me of the initial backlash to The Outsider and the rest of the Angry Young Men.

So I was delighted to have it brought to my attention (by the inimitable Jeff G.) that there has arisen something of a defense of Wilson and his work - in the New York Times, no less.

The full article has been reproduced below. However, before that, I have included an autobiographical review I wrote on The Outsider several years ago for the now defunct Booklist.com site (which can be revisited via the Wayback Machine here: http://web.archive.org/web/*/http://booklist.com):

I first encountered Wilson during my dreadful freshman year at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. A friend of mine from high school, Bill, who had wisely opted not to attend college, was working nearby at Taylor's Bookstore on Northwest Highway. Often I would stop by between, and sometimes during, classes to chat about what he was reading and see if anything interesting had come in.

One day Bill approached me as soon as I walked in the door, handed me a book, and told me to buy it and read it as soon as I could. High recommendation from someone as usually reticent towards praise as Bill. The book was The Mind Parasites by Colin Wilson, published in an unusual style by Wingbow Press. On the back there was an intriguing quote from Wilson stating the novel should attack reality like an axe cutting into a tree. That was good enough for me. I purchased the book and read it as an excuse to skip classes for the rest of the day. Late that night, when I closed the covers of the book, I realized that something as yet indefinable, but significant, had changed in my perspective on the world.

I returned to Taylor's the next day to discover what other books had been written by Wilson. There were several on the occult, a companion to The Mind Parasites called The Philosopher's Stone and a work called The Outsider. Of course I bought The Philosopher's Stone and also picked up The Outsider. Mid-way through The Philosopher's Stone, I became so stimulated by the ideas and the possibilities, the I opened up The Outsider to see if it explored the same issues.

I skipped past the Marilyn Ferguson foreword and the introduction by Wilson, to the first chapter, "The Country of the Blind". And from that first sentence, "At first sight, the Outsider is a social problem", and then, the quote from Barbusse ending with the line, "It is not a woman I want - it is all women, and I seek for them in those around me, one by one...", I was shot through with the hook, the line and the sinker for the "philosophy" of Colin Wilson. I finished The Philosopher's Stone and began a deep reading of The Outsider- neglecting most of my classes. When I did attend, it was as if I were participating in a surreal experiment of Outsiderism. What the professors were trying to teach me was utterly irrelevant to the life that was opening before me. And what my classmates wanted to discuss was even more banal and dead to me. I felt the "nausea" of Roquentin on an acute level, hours after having first read about it in The Outsider. And I came to the verge of recognizing that my college education was a complete sham when I got to chapter five, "The Pain Threshold" where Wilson cites the question by William James:

Does it not appear as if one who lived habitually on one side of the pain threshold might need a different sort of religion from one who habitually lived on the other?

For many years after, The Outsider and the "outsider series" were guiding and teaching texts to me. I took it upon myself to read as many of the primary works referenced as I could. I soon dropped out of college and began what was to be a life of working in book stores. During this time, I carried around a paper inscribed with these "conclusions" by Wilson:

- The Outsider wants to cease to be an Outsider.

- He wants to be 'balanced'.

- He wants to achieve a vividness of sense-perception.

- He would also like to understand the human soul and its workings.

- He would like to escape triviality forever, and be 'possessed' by a Will to power, to more life.

- Above all, he would like to know how to express himself, because that is the means by which he can get to know himself and his unknown possibilities.

Below this, were the two discoveries about the Outsider's 'way':

- That his salvation 'lies in extremes'.

- That the idea of a way out often comes in 'visions', moments of intensity, etc.

The Outsider (and the "Outsider Series") was one of the first books directly responsible, in an extreme and literal sense, for vast changes in the manner in which I lived my life. It was not just that my perspective was altered, but that important life decisions were generated and nurtured under its influence. That a book could have such power was simply amazing to one who had been educated such as I had been. Since then, thankfully, there have been many "life changing" books for me.

Ross MacDonald once remarked that there are certain writers that once were the heart and soul of your direction, that one day you come to be able to "see around" them. (Shakespeare, he added, was one that you could never "see around".) To a certain extent, I can now "see around" The Outsider - and not without a measure of sorrow. I still find myself returning to it often for "tuning". And I am still surprised when I dig into the roots of a current theme and discover what led me there initially, long ago, was a reference from The Outsider.

Although the book was written nearly fifty years ago, it still retains much of its relevance. I understand that there is a peculiar folly in "backward thinking", but in many ways the issues that were of concern to the "intellectuals" of the 1950s are even more prevalent today. Of course, the questions of value and meaning of human existence are bound up in the nature of what defines consciousness. However, the problems of alienation of self in a society that is morally, intellectually and theologically bankrupt have never been more critical. Perhaps this is why that of all of Wilson's books, The Outsider has been kept in print longer and more often than any other.

And, now, here is the NYT defense of Wilson that appeared August 17, 2005:

Philosopher of Optimism Endures Negative Deluge By Brad Spurgeon

Gorran Haven, Britain - Any intellectual who divides opinion as much as Colin Wilson has for almost 50 years must be onto something, even if it is only whether humans should be pessimistic or optimistic.

Mr. Wilson, who turned 74 in June and whose autobiography, "Dreaming to Some Purpose," recently appeared in paperback from Arrow, describes in the first chapter how he made his own choice. The son of working-class parents from Leicester - his father was in the boot and shoe trade - he was forced to quit school and go to work at 16, even though his ambition was to become "Einstein's successor." After a stint in a wool factory, he found a job as a laboratory assistant, but he was still in despair and decided to kill himself.

On the verge of swallowing hydrocyanic acid, he had an insight: there were two Colin Wilsons, one an idiotic, self-pitying teenager and the other a thinking man, his real self.

The idiot, he realized, would kill them both.

"In that moment," he wrote, "I glimpsed the marvelous, immense richness of reality, extending to distant horizons."

Achieving such moments of optimistic insight has been his goal and subject matter ever since, through more than 100 books, from his first success, "The Outsider," published in 1956, when he was declared a major existentialist thinker at 24, to the autobiography.

In an interview last month at his home of nearly 50 years on the Cornish coast, Mr. Wilson was as optimistic as ever, even though his autobiography and his life's work have come under strong attack in some quarters.

"What I wanted to do was to try to create a philosophy upon a completely new foundation," he said, sitting in his living room along with a parrot, two dogs and part of his collection of 30,000 books and as many records. "Whereas in the past optimism had been regarded as rather shallow - because 'oh well, it's just your temperament, you happen to be just a cheerful sort of person' - what I wanted to do was to establish that in fact it is the pessimists who are allowing all kinds of errors to creep into their work."

He includes in that category writers like Hemingway and philosophers like Sartre. In books on sex, crime, psychology and the occult, and in more than a dozen novels, Mr. Wilson has explored how pessimism can rob ordinary people of their powers.

"If you asked me what is the basis of all my work," he said, "it's the feeling there's something basically wrong with human beings. Human beings are like grandfather clocks driven by watch springs. Our powers appear to be taken away from us by something."

The critics, particularly in Britain, have alternately called him a genius and a fool. His autobiography, published in hardcover last year, has received mixed reviews. Though lauded by some, the attacks on it and Mr. Wilson have been as virulent as those he provoked in the 1950's after he became a popular culture name with the publication of "The Outsider."

That book dealt with alienation in thinkers, artists and men of action like T. E. Lawrence, van Gogh, Camus and Nietzsche, and caught the mood of the age. Critics, including Cyril Connolly and Philip Toynbee, hailed Mr. Wilson as a British version of the French existentialists.

His fans ranged from Muammar el-Qaddafi to Groucho Marx, who asked his British publisher to send a copy of his own autobiography to three people in Britain: Winston Churchill, Somerset Maugham and Colin Wilson.

"The Outsider" was translated into dozens of languages and sold millions of copies. It has never been out of print.

The Times of London called Mr. Wilson and John Osborne - another young working-class man, whose play "Look Back in Anger" opened about the same time "The Outsider" was published - "angry young men." That name was passed on to others of their generation, including Kingsley Amis, Alan Sillitoe and even Doris Lessing.

But fame brought its own problems for Wilson. His sometimes tumultuous early personal life became fodder for gossip columnists. He was still married to his first wife while living with his future second wife, Joy. His publisher, Victor Gollancz, urged him to leave the spotlight, and he and Joy moved to Cornwall.

But the publicity had done its damage. His second book, "Religion and the Rebel," was panned and his career looked dead.

Mr. Wilson said the episode had actually saved him as a writer, however. "Too much success gets you resting on your laurels and creates a kind of quicksand that you can't get out of," he said. "So I was relieved to get out of London."

He said his books were probably heading for condemnation in Britain anyway. "I'm basically a writer of ideas, and the English aren't interested in ideas," he said. "The English, I'm afraid, are totally brainless. If you're a writer of ideas like Sartre or Foucault or Derrida, then the general French public know your name, whereas here in England, their equivalent in the world of philosophy wouldn't be known."

He never lost belief in the importance of his work in trying to find out how to harness human beings' full powers and wipe out gloom.

"Sartre's 'man is a useless passion,' and Camus's feeling that life is absurd, and so on, basically meant that philosophy itself had turned really pretty dark," he said. "I could see that there was a basic fallacy in Sartre and Camus and all of these existentialists, Heidegger and so on. The basic fallacy lay in their failure to understand the actual foundation of the problem."

That foundation, he said, is that human perception is intentional; the pessimists themselves paint their world black.

Mr. Wilson has spent much of his life researching how to achieve those moments of well-being that bring insight, what the American psychologist Abraham Maslow called "peak experiences."

Those moments can come only through effort, concentration or focus, and refusing to lose one's vital energies through pessimism.

"What it means basically is that you're able to focus until you suddenly experience that sense that everything is good," Mr. Wilson said. "We go around leaking energy in the same way that someone who has slashed their wrists would go around leaking blood.

"Once you can actually get over that and recognize that this is not necessary, suddenly you begin to see the possibility of achieving a state of mind, a kind of steady focus, which means that you see things as extremely good." If harnessed by everyone, this could lead to the next step in human evolution, a kind of Superman.

"The problem with human beings so far is that they are met with so many setbacks that they are quite easily defeatable, particularly in the modern age when they've got too separated from their roots," he said.

Over the last year, he has been forced to test his own powers in this area. "When I was pretty sure that the autobiography was going to be a great success, and when it, on the contrary, got viciously attacked," Mr. Wilson said, "well, I know I'm not wrong. Obviously the times are out of joint."

Though "Dreaming to Some Purpose" was warmly received in The Independent on Sunday and The Spectator and was praised by the novelist Philip Pullman, the autobiography - and Mr. Wilson - received a barrage of negative profiles and reviews in The Sunday Times and The Observer. These made fun of the book's more eccentric parts, like his avowed fetish for women's panties.

As a measure of the passions that Mr. Wilson provokes, Robert Meadley, an essayist, wrote "The Odyssey of a Dogged Optimist" (Savoy, 2004), a 188-page book defending him.

"If you think a man's a fool and his books are a waste of time, how long does it take to say so?" Mr. Meadley wrote, questioning the space the newspapers gave to the attacks.

Part of Mr. Meadley's conclusion is that the British intellectual establishment still felt threatened by Mr. Wilson, a self-educated outsider from the working class.

"One of my main problems as far as the public is concerned is that I've always been interested in too many things," Mr. Wilson said, "and if they can't typecast you as a writer on this or that, then I'm afraid you tend not to be understood at all."

See also:

The Biography Project: Colin Wilson

The Colin Wilson Page

Lycaeum: Colin Wilson Interview

Colin Wilson: Psychological Ideas about Human Potential

The High and Low with Colin Wilson

Monday, August 15, 2005

Duke Digital Scriptorum: Ad* Access: J. Walter Thompson Company Competitive Advertisements Collection

"An image database of over 7,000 advertisements printed in U.S. and Canadian newspapers and magazines between 1911 and 1955."

The Ad*Access Project, funded by the Duke Endowment "Library 2000" Fund, presents images and database information for over 7,000 advertisements printed in U.S. and Canadian newspapers and magazines between 1911 and 1955. Ad*Access concentrates on five main subject areas: Radio, Television, Transportation, Beauty and Hygiene, and World War II, providing a coherent view of a number of major campaigns and companies through images preserved in one particular advertising collection available at Duke University. The advertisements are from the J. Walter Thompson Company Competitive Advertisements Collection of the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History in Duke University's Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.

Sunday, August 14, 2005

H. G. Wells: The World Brain

"We want... a universal organization and clarification of knowledge and ideas... what I have here called a World Brain, operating by an enhanced educational system through the whole body of mankind... a widespread world intelligence conscious of itself...

"The phrase "Permanent World Encyclopaedia" conveys the gist of these ideas. As the core of such an institution would be a world synthesis of bibliography and documentation with the indexed archives of the world. A great number of workers would be engaged perpetually in perfecting this index of human knowledge and keeping it up to date...

"Few people as yet, outside the world of expert librarians and museum curators and so forth, know how manageable well-ordered facts can be made, however multitudinous, and how swiftly and completely even the rarest visions and the most recondite matters can be recalled, once they have been put in place in a well-ordered scheme of reference and reproduction... There is no practical obstacle whatever now to the creation of an efficient index to all human knowledge, ideas and achievements, to the creation, that is, of a complete planetary memory for all mankind....

"This... foreshadows a real intellectual unification of our race. The whole human memory can be, and probably in a short time will be, made accessible to every individual. And... this new all-human cerebrum need not be concentrated in any one single place. It need not be vulnerable as a human head or a human heart is vulnerable. It can be reproduced exactly and fully, in Peru, China, Iceland, Central Africa, or wherever else seems to afford an insurance against danger and interruption. It can have at once, the concentration of a craniate animal and the diffused vitality of an amoeba..."

See also:

Wikipedia: World Brain

World Brain: The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia - H.G. Wells

H.G. Wells’s Idea of a World Brain: A Critical Re-Assessment - Boyd Rayward

Sunday, August 07, 2005

The Cornell Institute for Digital Collections: The Fantastic in Art and Fiction

F.R. Schellenberg. Freund heins Erscheinungen.

Winterthur : Heinrich Steiner und Comp., 1785. Page 0.16.

An unusual depiction of suicide, with death catching the man as he fires a pistol at his temple.

Amongst the many images that I seem to compulsively collect off the Web, line art, drawings and woodcuts of the Danse Macabre are at the top of the list. So it was Christmas morning for me to discover (via gmtPlus9) The Fantastic in Art & Fiction site hosted by The Cornell Institute for Digital Collections. Many of the images were entirely new to me and absolutely beautiful. You can click up to over 2ooK for detailed resolution.

Woodblock

E.-H. Langlois. Essai Historique,

Philosophique et Pittoresque sur les Danses des Morts.

The frontispiece of this pioneering study of the danse macabre theme

shows death attended by demons, leading a placid woman into grave.

The pose of both reminds one in fact of the chevalier at the ball,

with his waltzing partner.

Woodblock

J.A.S. Collin de Plancy. Dictionnaire Infernal. Paris : E. Plon, 1863. Page 20.

Ghost foretelling Alexander III’s death

The Fantastic in Art & Fiction is a digital curriculum unit developed by CIDC for John Anzalone, a Visiting Scholar at Cornell. It consists of an image-bank that is a visual resource for the study of the fantastic or of the supernatural in fiction and in art. While the site emerges from a comparative literature course on the topic at Skidmore College, it is also intended to open the door to consideration of some of the constant structures and patterns of fantastic literature, and the problems they raise. In this sense, the materials presented here may find a use among students in a variety of disciplines.

Saturday, August 06, 2005

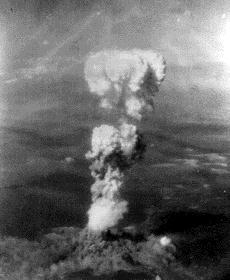

Original Child Bomb: Points for meditation to be scratched on the walls of a cave

The mushroom cloud billowing up 20,000 feet over Hiroshima on the morning of August 6, 1945 (Photo from U.S. National Archives, 77-AEC)

A nuclear weapon of the "Little Boy" type, the uranium gun-type detonated over Hiroshima. It is 28 inches in diameter and 120 inches long. "Little Boy" weighed about 9,000 pounds and had a yield approximating 15,000 tons of high explosives. (Copy from U.S. National Archives, 77-AEC)

Hiroshima, after the first atomic bomb explosion. This view was taken from the Red Cross Hospital Building about one mile from the bomb burst. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, Still Pictures Branch, Subject Files, "Atomic Bomb")

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II: A Collection of Primary Sources. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 162. Edited by William Burr - 202/994-7000 Posted - August 5, 2005

"Inspired by the photographic work "Hiroshima" by Japanese artist Hiromi Tsuchida, The Hiroshima Archive was originally set up to join the on-line effort made by many people all over the world to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing. The archive is intended to serve as a research and educational guide to those who want to gain and expand their knowledge of the atomic bombing."

Fragments from An Original Child Bomb, a poem by Thomas Merton. The complete text can be found at the end of a PDF from the documentary of the same name.

Points for meditation to be scratched on the walls of a cave.Original Child Bomb: The Film

1 In the year 1945 an Original Child was born. The name Original Child was given to it by the Japanese people, who recognized that it was the first of its kind.

13 The time was coming for the new bomb to be tested, in the New Mexico desert. A name was chosen to designate this secret operation. It was called “Trinity.”

14 At 5:30 A.M. on July 16th, 1945, a plutonium bomb was successfully exploded in the desert at Almagordo, New Mexico. It was suspended from a hundred foot steel tower which evaporated. There was a fireball a mile wide. The great flash could be seen for a radius of 250 miles. A blind woman miles away said she perceived light. There was a cloud of smoke 40,000 feet high. It was shaped like a toadstool.

15 Many who saw the experiment expressed their satisfaction in religious terms. A semi-official report even quoted a religious book-The New Testament, “Lord, I believe, help thou my unbelief.” There was an atmosphere of devotion. It was a great act of faith. They believed the explosion was exceptionally powerful.

22 On August 1st the bomb was assembled in an airconditioned hut on Tinian. Those who handled the bomb referred to it as “Little Boy.” Their care for the Original Child was devoted and tender.

25 On August 4th the bombing crew on Tinian watched a movie of “Trinity” (the Almagordo Test). August 5th was a Sunday but there was little time for formal worship. They said a quick prayer that the war might end “very soon.” On that day, Col. Tibbetts, who was in command of the B-29 that was to drop the bomb, felt that his bomber ought to have a name. He baptized it Enola Gay, after his mother in Iowa. Col. Tibbetts was a well balanced man, and not sentimental. He did not have a nervous breakdown after the bombing, like some of the other members of the crew.

26 On Sunday afternoon “Little Boy” was brought out in procession and devoutly tucked away in the womb of Enola Gay. That evening few were able to sleep. They were as excited as little boys on Christmas Eve.

31 At 3:09 they reached Hiroshima and started the bomb run. The city was full of sun. The fliers could see the green grass in the gardens. No fighters rose up to meet them. There was no flack. No one in the city bothered to take cover.

32 The bomb exploded within 100 feet of the aiming point. The fireball was 18,000 feet across. The temperature at the center of the fireball was 100,000,000 degrees. The people who were near the center became nothing. The whole city was blown to bits and the ruins all caught fire instantly everywhere, burning briskly. 70,000 people were killed right away or died within a few hours. Those who did not die at once suffered great pain. Few of them were soldiers.

35 It took a little while for the rest of Japan to find out what had happened to Hiroshima. Papers were forbidden to publish any news of the new bomb. A four line item said that Hiroshima had been hit by incendiary bombs and added: “It seems that some damage was caused to the city and its vicinity.”

36 Then the military governor of the Prefecture of Hiroshima issued a proclamation full of martial spirit. To all the people without hands, without feet, with their faces falling off, with their intestines hanging out, with their whole bodies full of radiation, he declared: “We must not rest a single day in our war effort ... We must bear in mind that the annihilation of the stubborn enemy is our road to revenge.” He was a professional soldier.

38 On August 9th another bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, though Hiroshima was still burning. On August 11ththe Emperor overruled his high command and accepted the peace terms dictated at Potsdam. Yet for three days discussion continued, until on August 14ththe surrender was made public and final.

40 As to the Original Child that was now born, President Truman summed up the philosophy of the situation in a few words. “We found the bomb” he said “and we used it.”

41 Since that summer many other bombs have been “found.” What is going to happen? At the time of writing, after a season of brisk speculation, men seem to be fatigued by the whole question.

[Interesting post/critique from Metafilter:

Sort of a digression, but this "oh-so-poetic/charming/mystical" Original Child Bomb name is a good example of the annoying tendancy some people have of making literal character-by-character translations of Chinese or Japanese words because they are supposed to be profound.P.S. I was also born on this day in 1945.

The name "original child bomb" was not "given to it by the Japanese people, who recognized that it was the first of its kind," as this page claims.

The word for "atom" is simply made of two kanji (Chinese characters), one meaning "original" or "basic" and one being a general diminutive that, yes, sometimes also means child. That is the way new Chinese words are formed, by putting together two or more characters in a way that makes sense, like "small basic thing" in the case of "atom." The translation is "atom bomb," OK? not "original child bomb," and there's no way that the people who coined the word meant it in any deeper sense. I'm sure this is an interesting movie, and I'd like to see it, but the Asian exoticism dripping off the title makes me want to gag.

posted by banishedimmortal]

Saturday, July 30, 2005

The Modern Word: Zak Smith's Illustrations For Each Page of Gravity's Rainbow

A screaming comes across the sky...Above him lift girders...the carriage, which is built on several levels...drunks, old veterans...hustlers...derelicts, exhausted women with more children...

From The Modern Word:

So I illustrated Gravity's Rainbow-- nobody asked me to, but I did it anyway. Most of the pictures are drawings-- ink on whatever paper was lying around, but there are also paintings (acrylic), photos I took, and experimental photographic processes. I tried to illustrate the passages as literally as possible-- if the book says there was a green Spitfire, I drew a green Spitfire. Mostly, I tried to make a series of pictures as dense, intricate, and rich as the prose in the book. The entire project was shown in the Whitney Museum's 2004 Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary Art and is now in the permanent collection of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

~Zak Smith

Monkey Paintings And Bad Writing

Jean Simon Chardin

Two of my guiltiest pleasures are collecting Monkey Paintings - especially those that have been passed off to critics as authentic human projects - and examples of bad writing - of which I have a huge personal collection.

Congo

In 1957, animal behaviorist Desmond Morris organized an exhibition of chimpanzee art at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts, including works by Congo. Critics reacted with a mixture of scorn and skepticism, but Picasso is recorded as having owned a painting by Congo.

Cheetah

As he stared at her ample bosom, he daydreamed of the dual Stromberg carburetors in his vintage Triumph Spitfire, highly functional yet pleasingly formed, perched prominently on top of the intake manifold, aching for experienced hands, the small knurled caps of the oil dampeners begging to be inspected and adjusted as described in chapter seven of the shop manual.

Dan McKay

Fargo, ND

A 43-year-old quantitative analyst for Microsoft Great Plains is the winner of the 23rd running of the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest. A resident of Fargo, North Dakota, McKay is currently visiting China, perhaps to escape notoriety for his dubious literary achievement.

His entry, extolling a subject that has engaged poets for millennia, may have been inspired by Roxie Hart of the musical "Chicago." Complaining of her husband's ineptitude in the boudoir, Roxie laments, "Amos was . . . zero. I mean, he made love to me like he was fixing a carburetor or something."

An international literary parody contest, the competition honors the memory (if not the reputation) of Victorian novelist Edward George Earl Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873). The goal of the contest is childishly simple: entrants are challenged to submit bad opening sentences to imaginary novels. Although best known for "The Last Days of Pompeii" (1834), which has been made into a movie three times, originating the expression "the pen is mightier than the sword," and phrases like "the great unwashed" and "the almighty dollar," Bulwer-Lytton opened his novel Paul Clifford (1830) with the immortal words that the "Peanuts" beagle Snoopy plagiarized for years, "It was a dark and stormy night."

The contest began in 1982 as a quiet campus affair, attracting only three submissions. This response being a thunderous success by academic standards, the contest went public the following year and ever since has attracted thousands of annual entries from all over the world.

My next favorite is in the Children's Category: Dishonorable Mentions

Because of her mysterious ways I was fascinated with Dorothy and I wondered if she would ever consider having a relationship with a lion, but I have to admit that most of my attention was directed at her little dog Toto because, after all, he was a source of meat protein and I had had enough of those damn flying monkeys.There are plenty more for your displeasure.

Randy Blanton

Murfreesboro, TN

(via /.)

Thursday, July 21, 2005

Square America: The Neighbors

There are much stranger realities than Disneyland in Southern California. The old industrial belt along the L.A. river has become this vast zone that consists of recycling and salvage yards. I met these immigrant workers there who break up computers all day long in a computer junkyard, in my mind typifying postmodern proletarians. You have to imagine a pile about 30 feet high of literally thousands of broken, defunct computers, and these guys with ball-peen hammers and screwdrivers and pliers listening to rock 'n' roll in Spanish, dismantling this stuff. There was one really funny guy who, when I asked him why he'd come to California, said, "To work in your high-tech economy," as he smashed an obsolete Macintosh.

- Mike Davis in interview with Mark Dery

Thursday, July 14, 2005

More Cormac: A Really Dangerous Idea

There's no such thing as life without bloodshed. I think the notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea. Those who are afflicted with this notion are the first ones to give up their souls, their freedom. Your desire that it be that way will enslave you and make your life vacuous.

- Cormac McCarthy