[source]

A week or so ago, as I was walking past Michael's Books, I stopped to check out the boxes of free books that they always leave outside. My attention was caught by the title of a tattered paperback, Man Alone: Alienation in Modern Society

One of the more influential books in my life was The Outsider by Colin Wilson, published in 1956. Strange things in the air from around 1955 to 1965. The issue of the "alienation of modern man" had a surprising relevance for popular culture: that there was a seething subculture disconnected from society; that the psychological effects of two world wars and the atomic bomb had undermined traditional values; that there was a "crisis" that must be attended to. The existential was cool. The world was burned-out, beat, whimpering in whispers. Something had to be done. Urgently. Unflinchingly.

The cover copy of Man Alone:

From Karl Marx to James Baldwin, from Dostoevsky to Ignazio Silone, and unflinching survey of one of the most critical dilemmas of our time.

The tone is now nostalgic, the narration of a film trailer from the same period. Sweet. 50s naive. You wonder which bourgeois-losers were publishing all those cowardly surveys of non-critical dilemmas. The smell of the old pages alone was that of serious thinking, intense conversation.

Scanning over the contents of Man Alone, I noted the final piece, The Hare and the Haruspex: A Cautionary Tale by Edward S. Deevey (originally published in The Yale Review, Winter 1960). It is a remarkable essay concerning the odd behavior of lemmings. From the distance of 50 years, it is still intellectually enchanting, something you might find from the Museum of Jurassic Technology, the style an engaging cross between Swift and Borges - subversive irony mixed with annotated counter-factology. Several times in the reading I had to slow down in order to parse the levels of satire and, for lack of a better term, scientific irony.

Deevey was a respected and influential paleolimnologist. Nothing in his other publications - that I can find - is similar in style to The Hare and the Haruspex.

I have included quite a few quotes below. Additionally, the piece led me to a moderately deeper consideration of the Analogy and Mythology of the Lemming. A few notes in this regard are also included.

[source]

From Man Alone: Alienation in Modern Society: Edited, with an introduction, by Eric and Mary Josephson, Dell Publishing, 1962. The Hare and the Haruspex: A Cautionary Tale by Edward S. Deevey [originally published in The Yale Review, Winter 1960]:

What is now suspected is that the lemmings are driven by some of the same Scandanavian compulsions that drove the Goths. At home, according to this view, they become depressed and irritable during the long, dark winters under the snow. When home becomes intolerable, they emigrate and their behavior is then described by the old Norse word, beserk.

As Caruso's vocal cords, suitably vibrated could shatter glassware, the whole of animate creation sometimes seems to pulsate with the supply of lemmings.

The reindeer, which ordinarily subsist on reindeer moss, acquire a taste for lemmings just as cattle use salt.

In his authoritative and starkly titled book, Voles, Mice and Lemmings, the English biologist Charles Elton summed up "this great cosmic oscillation" as "a reather tragic procession of refugees, with all the obsessed behavior of the unwanted stranger in a populous land, going blindly on to various deaths."

The diagnosis, if that is what it was, amounted to saying that the hares were scared to death, not by lynxes (for their bodies hardly ever showed claw-marks), but, presumably, by each other.

The Second World War was on at the time, and for a while no one remembered what Collett had said about the lemmings: "Life quickly leaves them, and they die from the slightest injury.... It is constantly stated by eyewitnesses, that they can die from their great excitement."

These Delphic remarks turned out to contain a real clue, which had been concealed in plain sight, like the purloined letter.

Well-trained in the school of Pasteur, or perhaps of Paul de Kruif, the investigators had been looking hard for germs, and were slow to take the hind of an atrophied liver, implying that shock might be a social disease like alcoholism. As such, it could be contagious, like a hair-do, without being infectious. It might, in fact, be contracted in the same way that Chevrolets catch petechial tail fins from Cadillacs, through the virus of galloping, convulsive anxiety. A disorder of this sort, increasing in virulence with the means of mass communication, would be just the coupled oscillator to make Gause's theory work. So theatrical an idea never occurred to Gause, though, and before it could make much progress the shooting outside the windows had to stop. About ten years later, when the news burst upon the world that hares are mad in March, it lacked some of the now-it-can-finally-be-told immediacy of the Smyth report on atomic energy, but it fitted neatly into the bulky dossier on shock disease that had been quietly accumulating in the meantime.

Keyed up by the stresses of crowded existence - he instanced poor and insufficient food, increased exertion, and fighting - animals that have struggled through a tough winter are in no shape to stand the lust that rises like sap in the spring. Their endocrine glands, which make the clashing hormones, burn like a schoolgirl making fudge, and the rodents, not being maple trees, have to borrow sugar from their livers. Cirrhosis lies that way, of course, but death from hypertension usually comes first.

Haruspicy, or divination by inspection of the entrails of domestic animals, is supposed to have been extinct for two thousand years, and no one know what the Etruscan soothsayers made of a ravaged liver. Selye would snort, no doubt, at being called a modern haruspex, but the omens of public dread are at least as visceral as those of any other calamity, and there are some sound Latin precedents - such as the geese whose gabbing saved Rome - for the view that emotion is communicable to and by animals. More recently, thoughtful veterinarians have begin to notice that neurotic pets tend to have neurotic owners....

From Wikipedia:

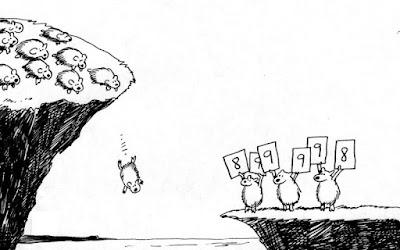

The myth of lemming "mass suicide" is long-standing and has been popularized by a number of factors. In 1955, Disney Studio illustrator Carl Barks drew an Uncle Scrooge adventure comic with the title "The Lemming with the Locket". This comic, which was inspired by a 1954 American Mercury article, showed massive numbers of lemmings jumping over Norwegian cliffs. Even more influential was the 1958 Disney film White Wilderness, which won an Academy Award for Documentary Feature, in which staged footage was shown with lemmings jumping into sure death after faked scenes of mass migration. A Canadian Broadcasting Corporation documentary, Cruel Camera, found that the lemmings used for White Wilderness were flown from Hudson Bay to Calgary, Alberta, Canada, where they did not jump off the cliff, but in fact were launched off the cliff using a turntable.

[source]

From Snopes:

Lemming suicide is fiction. Contrary to popular belief, lemmings do not periodically hurl themselves off of cliffs and into the sea. Cyclical explosions in population do occasionally induce lemmings to attempt to migrate to areas of lesser population density. When such a migration occurs, some lemmings die by falling over cliffs or drowning in lakes or rivers. These deaths are not deliberate "suicide" attempts, however, but accidental deaths resulting from the lemmings' venturing into unfamiliar territories and being crowded and pushed over dangerous ledges. In fact, when the competition for food, space, or mates becomes too intense, lemmings are much more likely to kill each other than to kill themselves.

Disney's White Wilderness was filmed in Alberta, Canada, which is not a native habitat for lemmings and has no outlet to the sea. Lemmings were imported from Manitoba for use in the film, purchased from Inuit children by the filmmakers. The Arctic rodents were placed on a snow-covered turntable and filmed from various angles to produce a "migration" sequence; afterwards, the helpless creatures were transported to a cliff overlooking a river and herded into the water. White Wilderness does not depict an actual lemming migration - no time are more than a few dozen lemmings ever shown on the screen at once. The entire sequence was faked using a handful of lemmings deceptively photographed to create the illusion of a large herd of migrating creatures.

Nine different photographers spent three years shooting and assembling footage for the various segments that comprise White Wilderness. It is not known whether Disney approved or knew about the activities of James R. Simon, the principal photographer for the lemmings sequence.

Nature documentaries are notoriously difficult to film, as wild animals are not terribly cooperative. Many nature shows and films of this era - including Disney's "True-Life Adventure" movies and TV's Wild Kingdom - staged events to capture exciting footage for their audiences. The sight of a few lemmings mistaking a lake or ocean for a stream and drowning after swimming out too far, or being pushed over a cliff during the frenzied rush of migration, has become the basis of a widespread belief that lemmings commit suicide en masse when their numbers grow too large.

[source]

From In Depth: ABC Science:

Back in the 1530s, the geographer Zeigler of Strasbourg, tried to explain these variations in populations by saying that lemmings fell out of the sky in stormy weather, and then suffered mass extinctions with the sprouting of the grasses of spring. Back in the 19th century, the Naturalist Edward Nelson wrote that "the Norton Sound Eskimo have an odd superstition that the White Lemming lives in the land beyond the stars and that it sometimes comes down to the earth, descending in a spiral course during snow-storms." But none of the Intuit stories mention the "suicide leaps off cliffs".

When these population explosions happen, the lemming migrate away from the denser centres. The migrations begin slowly and erratically, with an evolution from small numbers moving at night, to larger groups in the daytime. The most dramatic movements happen with the True Lemmings (also called the Norway Lemming). Even so, they do not form a continuous mass, but instead travel in groups with gaps of 10 minutes or more between them. They tend to follow roads and paths. Lemmings avoid water, and will usually scout around for a land crossing. But if they have to, they will swim. Their swimming ability is such that they can cross a 200 metre body of water on a calm night, but most will drown in a windy night.

So lemmings do have their regular wild fluctuations in population - and when the numbers are high, the lemmings do migrate.

The myth of mass lemming suicide began when the Walt Disney movie, Wild Wilderness was released in 1958. It was filmed in Alberta, Canada, far from the sea and not a native home to lemmings. So the filmmakers imported lemmings, by buying them from Inuit children. The migration sequence was filmed by placing the lemmings on a spinning turntable that was covered with snow, and then shooting it from many different angles. The cliff-death-plunge sequence was done by herding the lemmings over a small cliff into a river. It's easy to understand why the filmmakers did this - wild animals are notoriously uncooperative, and a migration-of-doom followed by a cliff-of-death sequence is far more dramatic to show than the lemmings' self-implemented population-density management plan.

2 comments:

Amazing. Thank you!

Amazing! I never even once questioned lemming mass suicide, but now I definitely know better. And I'll never hear the word 'turntable' the same way again...

Thank you!

Post a Comment