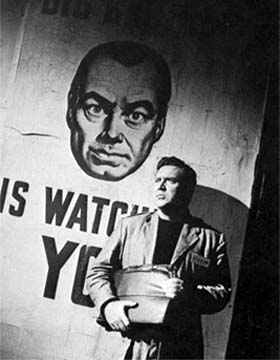

The argument turned to an issue explored by the late Neil Postman in his excellent work Amusing Ourselves to Death. He points out some of the fundamental differences between the vision of the future proposed by George Orwell, in 1984, and Aldous Huxley, in Brave New World:

This brought to mind a fascinating discussion on signal vs. noise and filters on Chris Anderson's blog, The Long Tail (which is an exploration of issues surrounding his ground-breaking article of the same name in Wired):

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared that the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.

Is the Long Tail full of crap? by Chris Anderson

One of the most frequent mistakes people make about the Long Tail is to assume that things that don't sell well are "not as good" as things that do sell well. Or, to put it another way, they assume that the Long Tail is full of crap. After all, if that album/book/film/whatever were excellent, it would be a hit, right?

Well, in a word, no. Niches operate by different economics than the mainstream. And the reason for that helps explain why so much about Long Tail content is counterintuitive, especially when we're used to scarcity thinking.

First, let's get one thing straight: the Long Tail is indeed full of crap. But it's also full of works of refined brilliance and depth--and an awful lot in between. Exactly the same can be said of the Web itself. Ten years ago, people complained that there was a lot of junk on the Internet and, sure enough, any casual surf quickly confirmed that. Then along came search engines to help pull some signal from the noise and finally Google, tapping the wisdom of the crowd itself to turn a mass of incoherence into the closest thing to an oracle the world has ever seen.

On a store shelf or in any other limited means of distribution, the ratio of good to bad matters because it's a zero sum game. Space for one eliminates space for the other. Prominence for one obscures the other. If there are ten crappy toys for each good one in the aisle, you'll think poorly of the toy store and be discouraged from browsing. Likewise it's no fun to flip through bin after bin of CDs if you haven't heard of any of them.

But where you have unlimited shelf space, it's an infinite sum game. The billions of crappy web pages about whatever are not a problem in the way that billions of crappy CDs on the Tower Records shelves would be. Inventory is "non-rivalrous" and the ratio of good to bad is simply a signal-to-noise problem, solvable with information tools.

Which is to say it's not much of a problem at all. You just need better filters, such as recommendations and good search engines. The fact that screens 10 and beyond of your Google search results are unhelpful doesn't matters because screens 1-3 are so useful. The noise is still out there, but Google allows you to effectively ignore it. Filters rule!

The following is this expressed graphically. As you go down the Long Tail the signal-to-noise ratio gets worse. Thus the only way you can maintain a consistently good enough signal to find what you want is if your filters get increasingly powerful.This leads to the key to what's different about Long Tails. They're not pre-filtered by the requirements of distribution bottlenecks and all that entails (editors, studio execs, A&R guys and Wal-Mart purchasing managers). As a result their components vary wildly in quality, just like everything else in the world.

One way to describe this (using the same language of information theory that brought us signal-to-noise ratios) would be to say that Long Tails have a "wide dynamic range" of quality: awful to great. By contrast, the average store shelf has a relatively narrow dynamic range of quality: mostly average to good (there's some really great stuff, but much of that is too expensive for the average retail shelf; niches exist at both ends of the quality spectrum).

So tails have a wide dynamic range and heads have a narrow dynamic range. Like this:

Note that you have high-quality goods in every part of the curve, from top to bottom. Yes, there are more low-quality goods in the tail and the average level of quality declines as you go down the curve. But with good filters averages don't matter. It's all about the diamonds, not the rough, and diamonds can be found anywhere.

Before I go on I should say a word about the confusing terms "high quality" and "low quality". They are, of course, entirely subjective. Here are some examples of criteria people might use to value content:

"High quality":

- Addresses my interests

- Well made

- Fresh

- Substantive

- Compelling

"Low quality":

- Not for me

- Badly made

- Stale

- Superficial

- Boring

Note that all of those are entirely in the eye of the beholder; there are no absolute measures of content quality. One person's "good" could easily be another's "bad"; indeed, it almost always is. I like economics papers, but I have friends who like Maxim. They find my stuff boring; I find their stuff superficial (except for those Jessica Alba pics).

This is why niches are different. Your noise is my signal. If a producer intends something to be absolutely right for one audience it will by definition be wrong for another. The compromises necessary to make something appeal to everyone mean that it will almost certainly not appeal perfectly to anyone--that's why they call it the lowest common denominator.

Is South Park badly made or brilliant? Once upon a time some network exec had to answer that question for all of us before it could get distribution. Cable lowered the bar and now Netflix and the web are lowering it further. In a Long Tail world each of us answers the quality question for ourselves and the marketplace sorts it out.

All this leads to three counterintuitive lessons of the Long Tail.

- Niche content can be of higher quality than hit content.

- It doesn't matter how much junk there is around those gems; with good filters, the average level of quality is irrelevant.

- You can charge more for high-quality niche content because it is so well-suited to its audience.

More on the signal/noise debate from the Long Tail

Change This PDF of The Long Tail

No comments:

Post a Comment