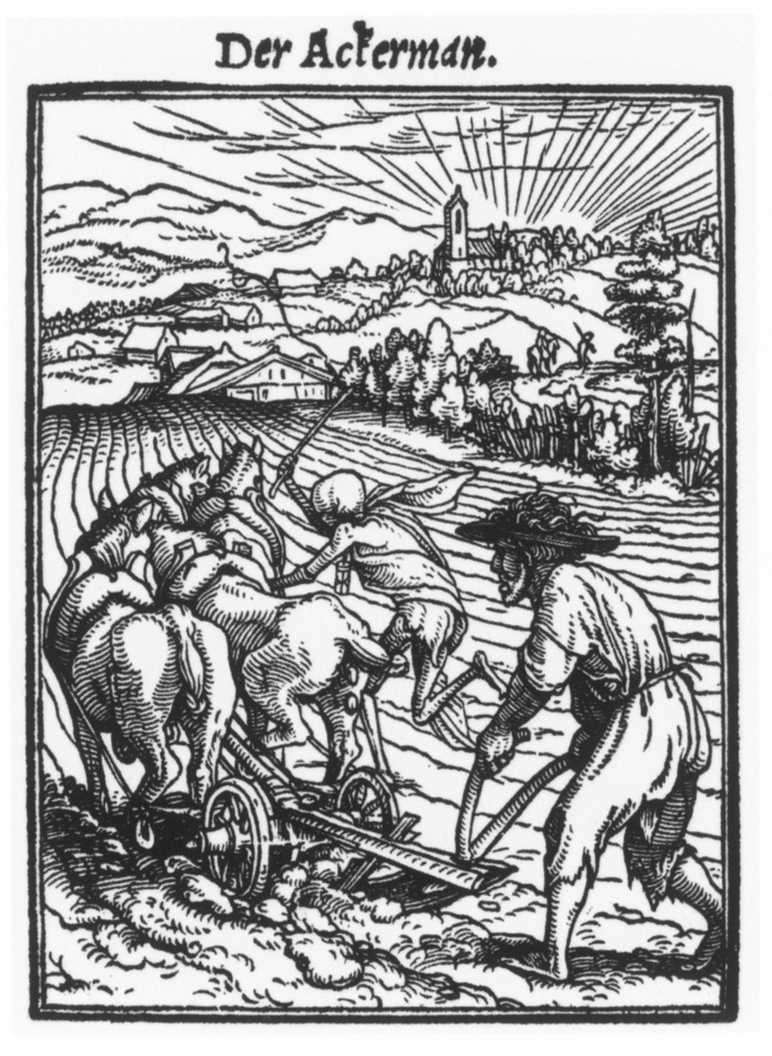

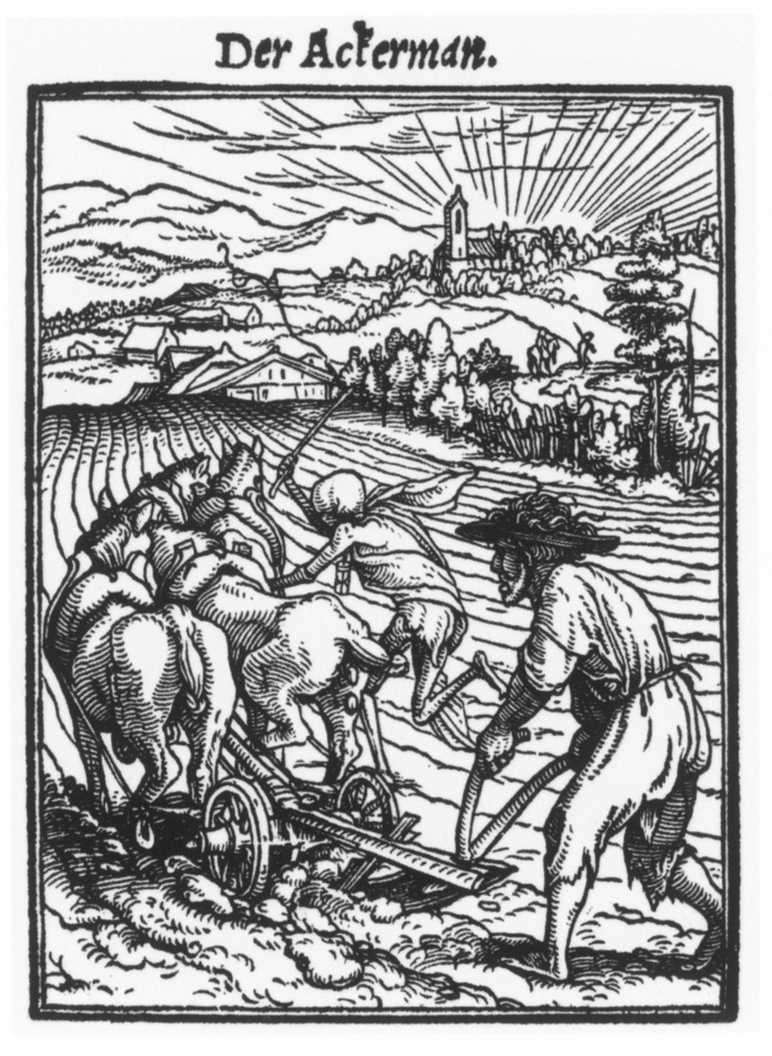

The Plowman from Dance of Death

The Plowman from Dance of Death

Hans Holbein, the Younger, 1524-26

Woodcut, 65 x 48 mm I received the August issue of Vanity Fair the other day with Martha Stewart on the cover with an ugly dog. Was tempted to not even open it up but thought I would check out what James Wolcott had to say, if anything. Big Media not facing up to Iraq. Alright. Ads. Tom Cruise. Michael Jackson. Start to close the magazine and then, there is a picture of Cormac McCarthy staring right out at me. His first interview in 13 years - and, reportedly, the second one ever. Looked back to the front cover to see where I missed the headline about this. And it is nowhere to be found. Fucking amazing. Just for amusement's sake, here are the headlines that were more important and earth-shattering than the Second Interview Cormac McCarthy Has Ever Given In His Life:

Dominck Dunne: Has Tom Cruise Lost His Marbles?

The N.Y.P.D. Cops Accused of Killing for the Mob (I'll give them this one.)

How Elle Macpherson Went from Bikini Queen to Lingerie Mogul!

The Bitter Battle over the Jimmy Choo Shoe Empire

The Brawl That Shook the Guggenheim

Out of the Doghouse, But Still Under House Arrest, Martha Stewart. Exclusive! The Big Post-Prison Interview!

Anyway, the article/interview is, as you would expect, fascinating and intriguing. There are a lot of personal details about McCarthy that I had never read before and some amusing childhood photographs - Little Cormac dressed as a cowboy with guns. Turns out that he's been spending the last few years at the

Santa Fe Institute attending lectures and reading papers. And, of course, writing. There is a new book,

No Country For Old Men, due out next week.

The article/interview isn't online yet. And the only notice I could find was from the

Seattle Post Intelligencer:

Reclusive novelist Cormac McCarthy gives first interview in 13 years

The reclusive Southwest novelist -- who rocketed to best-seller prominence in 1992 with the prize-winning "All the Pretty Horses" -- gives his first interview in 13 years in the August issue of Vanity Fair, which goes on sale Tuesday.

Journalist Richard B. Woodward fills in many intriguing personal details about the 72-year-old novelist in "Cormac Country," but the writer himself remains tightly circumspect, especially on his own work. "No Country for Old Men," McCarthy's first novel in seven years, will be released on July 19 by Alfred A. Knopf. McCarthy now lives in a luxe section of Santa Fe after years of poverty in El Paso, has a wife several decades younger and a 6-year-old son.

About the closest McCarthy comes to discussing his work is this comment on why his novels, including his new one, are so violent: "Most people don't ever see anyone die. It used to be if you grew up in a family you saw everybody die. They died in their bed at home with everyone gathered around. Death is the major issue in the world. For you, for me, for all of us. It just is. To not be able to talk about it is very odd."

Other Sources:

The Cormac McCarthy HomepagesWikipedia: Cormac McCarthyBiography Project: Cormac McCarthyLanguage & the Dance of Time in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian