pleading at the table of sacred love, represented as a judge.

From Penn State Univesity Library

I hereby publicly declare that all entries on this weblog, The Laughing Bone, are the sole creation of the fiery mind of Scot Casey - unless otherwise noted by attribution or quotation - and, that I will make no use of any of the works of Mr. Charles "Bonesy" Jones - beyond those which already exist on this weblog.

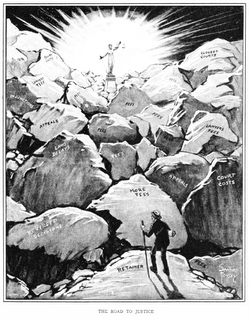

That being so awkwardly stated and with no explanatory gloss, allow me to encourage all of you that have any interest in leaving behind some vestige of being, some artifact of soul, after you have shuffled off this mortal coil (Wm. Shakespeare), to gird up your loins, plug your asshole and engage in some dire conference with a lawyer to prepare a SIMPLE WILL. Be sure to bring plenty of patience and lucre.

Henceforth, all work published under the name Scot Casey on this blog is under a Creative Commons license:

Creativity and innovation rely on a rich heritage of prior intellectual endeavor. We stand on the shoulders of giants by revisiting, reusing, and transforming the ideas and works of our peers and predecessors. Digital communications promise a new explosion of this kind of collaborative creative activity. But at the same time, expanding intellectual property protection leaves fewer and fewer creative works in the "public domain" — the body of creative material unfettered by law and, to quote Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, "free as the air to common use."

Until 1976, creative works were not protected by U.S. copyright law unless their authors took the trouble to publish a copyright notice along with them. Works not affixed with a notice passed into the public domain. Following legislative changes in 1976 and 1988, creative works are now automatically copyrighted. We believe that many people would not choose this "copyright by default" if they had an easy mechanism for turning their work over to the public or exercising some but not all of their legal rights. It is Creative Commons' goal to help create such a mechanism.

Now for a few quotes that have educated, amused and sustained me over the last year or so:

Intestate Succession - From Britannica.com

In the law of inheritance, succession to property that has not been disposed of by a valid last will or testament. Although laws governing intestate succession vary widely in different jurisdictions, they share the common principle that the estate should devolve upon persons standing in some kinship relation with the decedent. Modern laws of intestacy have tended not to emphasize the traditional concern that property be kept within the bloodline through which it came to the decedent. Modern practice also tends to favour the rights of the surviving spouse, whether or not he or she is regarded as kin, and (in most jurisdictions) to ease restrictions on inheritance by illegitimate children.

From The Tragedy of King Richard the Third. Act IV. Scene IV:

Duch.

Why should calamity be full of words?

Q. Eliz.

Windy attorneys to their client woes,

Airy succeeders of intestate joys,

Poor breathing orators of miseries!

Let them have scope: though what they do impart

Help nothing else, yet do they ease the heart.

Duch.

If so, then be not tongue-tied: go with me,

And in the breath of bitter words let’s smother

My damned son, that thy two sweet sons smother’d.

[A trumpet heard.]

The trumpet sounds: be copious in exclaims.

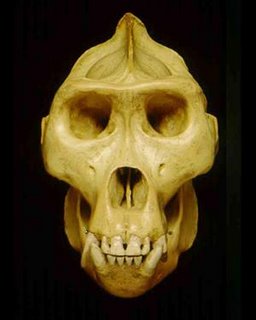

From Human Evolution

From Human EvolutionHamlet.

There's another: why may not that be the skull of a lawyer? Where be his quiddits now, his quillets, his cases, his tenures, and his tricks? why does he suffer this rude knave now to knock him about the sconce with a dirty shovel, and will not tell him of his action of battery? Hum! This fellow might be in's time a great buyer of land, with his statutes, his recognizances, his fines, his double vouchers, his recoveries: is this the fine of his fines, and the recovery of his recoveries, to have his fine pate full of fine dirt? will his vouchers vouch him no more of his purchases, and double ones too, than the length and breadth of a pair of indentures? The very conveyances of his lands will hardly lie in this box; and must the inheritor himself have no more, ha?

Horatio.

Not a jot more, my lord.

Hamlet.

Is not parchment made of sheep-skins?

Horatio.

Ay, my lord, and of calf-skins too.

Hamlet.

They are sheep and calves which seek out assurance in that. I will speak to this fellow.- Whose grave's this, sirrah?

Related Discussion from Mauled Again

Courts have long held under principles of public policy, that a decedent cannot direct the destruction of property after death. Thus, even though a person, while alive, can light a proverbial cigar with a proverbial rolled up $20 bill, one cannot order one's cash burned after death. Nor, according to several cases, can one order the razing of one's home (even if one could do so during lifetime), and this is an issue aside from permits and environmental concerns.

So in the classic hypothetical, when the decedent dies, love letters written to the decedent are found. Make the hypothetical interesting by identifying the writer as either a famous person or, better yet, someone whose position and status makes those letters scandalous (as if today there's much left that can fall within that term). So, however one wants to set up the facts, do so in a way that gives the love letters value. In our world of Warhol minutes, reality TV, and gossip run amok, it's unlikely that any love letters would lack value. The same is true of any other sort of letter (though love letters makes the hypothetical more interesting and gets the students' interest). The more secrets, the deeper the secrets, the more widespread those impacted or interested in the secrets, the higher the value of the email or other correspondence. I suppose that for celebrities' correspondence, the value reaches a peak and the issue is more likely to be litigated.

So if a decedent cannot order the burning of cash or the razing of a home, should a decedent be permitted to order the destruction of correspondence that has value? If the answer is yes, then those carving out an exception need to define the line, and I'm not convinced that the line can easily be drawn. Would it extend to home movies? Audiotapes? Photographs? Art work?

Surely one can think of reasons that the decedent would want the material destroyed, but then again, the decedent could have destroyed the material while alive. Except that destroying email on the email server of a commercial internet provider isn't easily accomplished, and might not be possible with emails less than 30 or 60 or 90 days old. But one also can think of reasons OTHER people would want the decedent's email and other materials destroyed: as one person pointed out (archived at Politech), "the emails might reveal the secret abortion of the sister or the secret first marriage of the father."

Digital technology puts yet another wrinkle on the issue. Paper correspondence sent to another person is in that other person's hands, and unless a photocopy was retained, it is beyond the reach of the decedent. The decedent cannot destroy it. Nor do the decedent's executor and beneficiaries have access (though, of course, the recipient's executor and beneficiaries might get their hands on it). With email, not only is the incoming correspondence on the server or computer, so too is the outgoing correspondence, or at least some of it is. Keep in mind that email is far more voluminous than is paper correspondence, perhaps by an order of magnitude.

Putting a direction in a will to destroy "love letters" could be counterproductive because wills aren't private. They become public when probated. "Destroy the love letters ....." or "Burn the letters received from ...." language would create all sorts of an uproar, and even if the contents never became public, the existence of the material would fuel the rumor mill for a long time, even if the decedent was not a national or international celebrity. After all, each one of us is a celebrity in our own little world. And, of course, "burn all correspondence" is overkill that by reaching legitimately retained financial and other information necessary for tax return and other compliance would give a court even more reason to hold to the principle that one cannot order the destruction of property after death.

It makes more sense to direct all property to a pre-existing trust and to give direction to the trustee (assuming, of course, that there is a right to order destruction of property). If the will inadvertently or deliberately incorporates the trust by reference, all bets are off because the trust is part of the probated will rather than a separate entity.

No comments:

Post a Comment