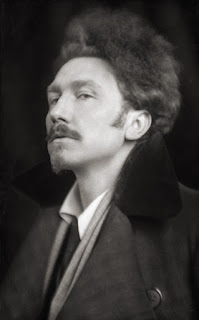

Just discovered the photography of E. O. Hoppe (via gmtPlus9 (-15)).

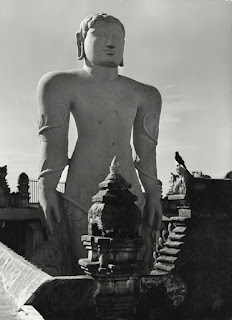

What was in the atmosphere of photography between 1914 and 1945 that created so many iconic images? Not to take anything away from the stunning talents of Hoppe, but there seems almost a quality of film... something in the recent development of handhelds? More: a charged quality of light and a weird artificiality in focus. Much of it evocative to me of tilt shift photography where the image appears as a miniature scale model of the real. But with Hoppe and, dare I say, Riefenstahl, there is a larger than life tilt shift, images of more substantial statuary sorts of beings. I feel as if I am stepping lightly around the aesthetic criteria for German Expressionism - and while there is a undeniable resonance, there is something more... a staging, perhaps, for a future aesthetic that was never allowed to emerge.

From the website biography:

How is it possible that a photographer so famous in the early modern period and so prolific between 1907 and 1939 came to be known only in a limited way to a few photo-cognoscenti? The art journals of the 1920s in Britain, Europe, and the US paid far more attention to Hoppé’s exhibitions and publications than they did those of Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Edward Steichen, Paul Outerbridge, Edward Weston, or others to whom historians point as founders of modernist photography. The answer would seem to be a combination of simple bad timing, and a few unfortunate turns in Hoppé's personal history that caused the bulk of his work to be locked away in archives in London and in Wiesbaden, Germany, for most of the second half of the last century.What those "unfortunate turns" were, I have been unable to discern through the most obvious internet sources.

The following images are from the hauntingly titled, The Face of Mother India 1935:

Be sure to take look at the other galleries:

The Book of Fair Women

Deutsche Arbeit

Typologies

By the late teens Hoppé had spent over a decade making portrait photographs of Britain’s high society. Perhaps to challenge his skills as with Professor Higgins, Hoppé began making portraits of London’s street types. English charladies, maids, and market sellers were at first brought into his studio and photographed. Later he sought them on the street. In 1922 he published a group of these studies in his book, Taken From Life with text by J. D. Beresford and again in 1926 the made a second book, London Types; Taken from Life with texts W. Pett Ridge. In the sprit of G. B. Shaw’s experiment, Hoppé continued a lifelong interest in making portraits of the ordinary working man and woman in each of the diverse cultures he encountered.

An interesting aside is that Shaw’s Pygmalion later became the highly successful musical My Fair Lady. It’s set and costume design was created by another photographer, Cecil Beaton, who had directly modeled the style of his photographic career on that of E. O. Hoppé.

Amazon Link: E. O. Hoppe's Amerika: Modernist Photographs from the 1920s