McCarthy’s tendency for pastiche does more than invest his work with a literary gamesmanship. By pulling together an ever-shifting assemblage of references, he constructs the bones of his world while offering a critique of its sources. So while one may identify The Road’s preoccupation with the preference of suicide over rape and consumption by savages as one of the more virulently racist tropes of the classic “Indian-hating” western, its usage here imparts a new horror, even as it calls into question the over-arching metaphor of savagism. After all, in The Road, the savages are us. Likewise, when the title of Kris Kristofferson’s song “Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends” pops up as the man ponders the fate of his son, it conveys a new poignancy, striking the reader as a wayward remnant of the pre-apocalypse. This is the effect of many of McCarthy’s borrowings in The Road. Unlike the playful vigor imparted by his pastiche-work in former novels, here it conveys a draining of vitality, as if these rags of meaning are all that remain to cover the naked desolation of the world he’s created. It is a beautifully achieved illusion, and a testament to the seamlessness of McCarthy’s craft.

Monday, October 23, 2006

These Rags of Meaning Are All That Remain to Cover the Naked Desolation

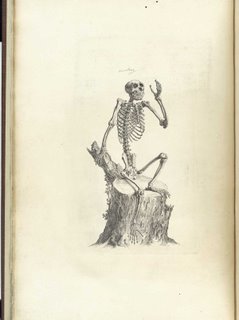

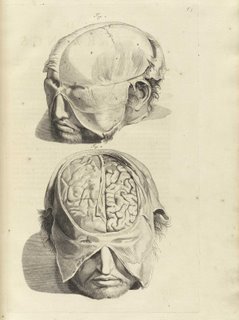

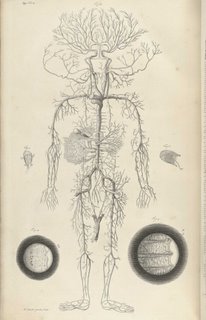

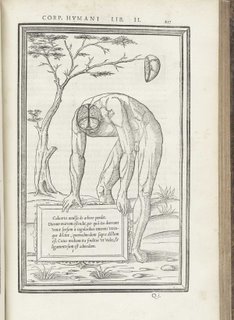

Osteographica: Historical Anatomies on the Web

Author: Cheselden, William (1688-1752).

Author: Cheselden, William (1688-1752).Title: Osteographia, or The anatomy of the bones.

Publication Information: London: [William Bowyer], 1733.

While getting up to date on the always excellent, Giornale Nuovo, I clicked through to the National Library of Medicine's Historical Anatomies on the Web.

Images have been selected from the following anatomical atlases in the National Library of Medicine's collection. Each atlas is linked to a brief Author & Title Description, which offers an historical discussion of the work, its author, the artists, and the illustration technique. The Bibliographic Information link provides a bibliographical description of the atlas, so users will know which edition was scanned and if there are any characteristics special to the Library's copy.There is such a concentration of sublime imagery here (many featured prominently in the Dream Anatomy Online Exhibition) that you could almost choose at random to provide stunning examples. However, a few personal favorites:

Author: Bidloo, Govard (1649 - 1713).

Author: Bidloo, Govard (1649 - 1713).Title: Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams.

Publication Information: Amsterdam: Weduwe van Joannes van Someren, et al., 1690.

Author: Cowper, William (1666-1709).

Author: Cowper, William (1666-1709).Title: The anatomy of humane bodies.

Publication Information: Oxford :

Printed at the Theater, for Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford, 1698.

Author: Estienne, Charles (ca. 1504-ca. 1564).

Author: Estienne, Charles (ca. 1504-ca. 1564).Title: De dissectione partium corporis humani libri tres.

Publication Information: Paris: Simon Colinaeus, 1545.

Author: Spiegel, Adriaan van (1578-1625) and Casseri, Giulio (ca. 1552-1616).

Author: Spiegel, Adriaan van (1578-1625) and Casseri, Giulio (ca. 1552-1616).Title: De formato foetu liber singularis.

Publication Information: Padua: Io. Bap. de Martinis & Livius Pasquatus, [1626].

Saturday, October 07, 2006

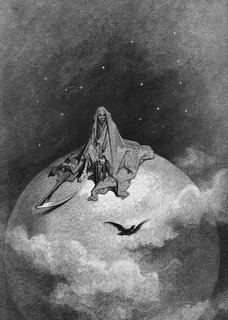

When the Pulse has been nailed upon the crossbeams.

From Edward Dahlberg's Can These Bones Live:

The critic is the Sancho Panza to his master, our Lord Don Quixote, the artist. Sancho is no bread, butter and beer realist. He too sees and knows with the magical folly of the heart that there is knowledge before reason and science, a secret wisdom that is prior to logic - the vibrant god-telling PULSE. "There are reasons of the heart of which Reason knows nothing," said Pascal.

There are no abstract truths - no Mass Man, no proletariat. There is only Man. When the Pulse has been nailed upon the crossbeams, lo, Reason gives up its viable breath and becomes a wandering ghostly Error. Truth and folly are ever about to expire, so that we, like our beloved Sancho Panza, kneeling at the deathbed of Don Quixote, must always be ready to receive the holy communion of cudgels and distaffs for the rebirth of the Pulse.

Sunday, October 01, 2006

Men in a bathysphere at sea-bed may transmit.

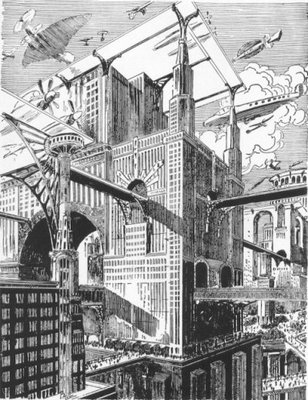

Aerodrome of the future.

Aerodrome of the future.(published ca. 1935-1938)

Captain Eyston's car 'Thunderbolt'.

Captain Eyston's car 'Thunderbolt'.(published ca. 1935-1938)

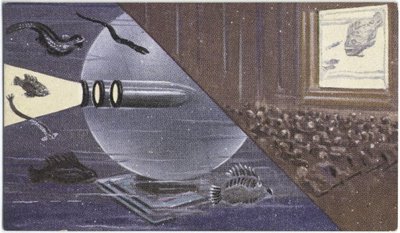

What inspired copy-writer came up with this future-conjuring sentence:

What inspired copy-writer came up with this future-conjuring sentence:Men in a bathysphere at sea-bed may transmit to the home set or to the cinema scenes taking place at the bottom of the ocean.Somewhere the skull of Hugo Gernsback is smiling. And then one thing lead to another and the Gallery of Frank R. Paul's Artwork

The Future of Radio. Illustration by Frank R. Paul,

The Future of Radio. Illustration by Frank R. Paul,in Radio For All, Hugo Gernsback, 1922

Doctor Hackensaw's Secrets. Illustration by Frank R. Paul,

Doctor Hackensaw's Secrets. Illustration by Frank R. Paul,No. 12: The Secret of the Philosopher's Stone,

Science and Invention, Jan. 1923

Then I looked behind me and saw the city. The books on Thirties design were in the trunk; one of them contained sketches of an idealized city that drew on Metropolis and Things to Come, but squared everything, soaring up through an architect's perfect clouds to zeppelin docks and mad neon spires. That city was a scale model of the one that rose behind me. Spire stood on spire in gleaming ziggurat steps that climbed to a central golden temple tower ringed with the crazy radiator flanges of the Mongo gas stations. You could hide the Empire State Building in the smallest of those towers. Roads of crystal soared between the spires, crossed and recrossed by smooth silver shapes like beads of running mercury. The air was thick with ships: giant wing-liners, little darting silver things (sometimes one of the quicksilver shapes from the sky bridges rose gracefully into the air and flew up to join the dance), mile-long blimps, hovering dragonfly things that were gyrocopters...

Image of the Modern City

Image of the Modern Cityfrom the set of the 1930 musical, Just Imagine.

From INVENTING MODERN:

AND CREATING AN UNEXPECTED FUTURE

Image from a 1928 issue of Amazing Stories.

Image from a 1928 issue of Amazing Stories.From INVENTING MODERN:

AND CREATING AN UNEXPECTED FUTURE

Saturday, September 30, 2006

A gift that cannot be given away ceases to be a gift.

Searching through aspects of the phrase "the perfect day", I came across this image:

There was certainly a sexual element to it. But more: a quality of plenty, of abundance, surplus. I began to consider the meaning of the Act of Pouring. And, the feminine attachments to this act. Economic and gender interpretations seemed to merely cloud the surface. Underneath there was a quality of radiance, an over-flowing. Witness Vermeer's Milkmaid:

Outside of the famous and undeniable radiance of the painting itself, the Milkmaid's act of pouring has its own internal luminescence. Specifically a woman in the act of pouring liquid from one vessel to another. It was absolutely hypnotic to me. And I couldn't precisely figure it out. So I collected more images:

Eduard Manet, Woman Pouring Off Water (1858)

Eduard Manet, Woman Pouring Off Water (1858) From Wikipedia:

From Wikipedia:Temperance (Italian: La Temperanza) is a Major Arcana Tarot card, numbered VI or VII in the oldest Italian decks, but XIV in the Tarot de Marseille and in most contemporary decks. In the Thoth Tarot and decks influenced by it, this card is called Art rather than Temperance.

Temperance is almost invariably depicted as a person pouring liquid from one receptacle into another. Historically, this was a standard symbol of the virtue temperance, representing the dilution of wine with water. In many decks, the person is a winged angel, usually female or androgynous, and stands with one foot on water and one foot on land.

Temperance? What was the connection between the feminine act of pouring and temperance? Why was temperance represented as an act of pouring between one vessel and another?

Temperance? What was the connection between the feminine act of pouring and temperance? Why was temperance represented as an act of pouring between one vessel and another?What is suggested is an act of allotment, a distribution of substance, a pouring off of a "proper share". Implications of balance, discipline and ritual are just underneath. The female who pours knows precisely how much there is in total, where the plenty ends, and how much to pour off each time. But at the core of it, and this is what has fascinated me, was the idea of the gift. Being the holder of the vessel, she knows what "plenty" means. She is the keeper of the abundance, the radiance. It is her understanding that determines "what shall be given to each"; what the Gift shall be. These sentences just pound upon the biggest drum in my brain. Voodoo thoughts.

And this leads me to Lewis Hyde's excellent book, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property:

There is much more to say about Art and the Gift. About the Myth of Scarcity. About the commodification of art. And what role Temperance has to play in all of it. It is worth remarking in passing that the Temperance card in the Tarot was one called Art. Perhaps in another post.

That art that matters to us - which moves the heart, or revives the soul, or delights the senses, or offers courage for living, however we choose to describe the experience - that work is received by us as a gift is received. Even if we have paid a fee at the door of the museum or concert hall, when we are touched by a work of art something comes to us which has nothing to do with price.

A gift that cannot be given away ceases to be a gift. The spirit of a gift is kept alive by its constant donation. If this is the case, then the gifts of the inner world must be accepted as gifts in the outer world if they are to retain their vitality. Where gifts have no public currency, therefore, where the gift as a form of property is neither recognized nor honored, our inner gifts will find themselves excluded from the very commerce which is their nourishment. Or, to say the same thing from a different angle, where commerce is exclusively a traffic in merchandise, the gifted cannot enter into the give-and-take that ensures the livelihood of their spirit.

What is important to say here and now though is that when one is given a magnificent gift, one that exceeds all possibility of ever being "re-turned", then the qualities of temperance become vital. It is the correct mixing of metals that tempers a sword into greater strength. It is proper balance of mental states that defines our psychological temper. Temperance grants us understanding to know the balance between the give-and-take, what it means to for-give and for-get, what the true meaning of the gift is. Under the burden of a magnificent gift, it is simply crucial to maintain temper.

The Fiery Angel stands before you pouring everything, Everything, from one vessel into another. That you might receive something from that is a True Gift. And I believe with all of my being that in the end, you MUST find a way to give it back - in spite of, even because of, any temporal law or repercussion. Else, you lose everything that makes your life worth living. Literature, poetry, painting, sculpture, music will come to mean nothing. You die inside. The Culture dies.

George Steiner, in a Guardian review about Vermeer, remarked that:

There is sadness as well, and an intimation of irreparable loss. What would Vermeer make of the brutal trash, of the self-advertising cliches which currently pass for art? Of the fake machine-guns, ripped sacking or virtually empty galleries in the New Tate? Just what has made impossible for us the creation, the communication of the weight, of the radiance of things and of their human custodians so abundant in Vermeer? Whom are we fooling but ourselves?

in India's northwestern state of Rajasthan.

REUTERS/Kamal Kishore

Friday, September 29, 2006

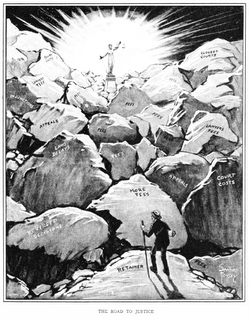

Where Have I Been? Conversing with the Skull of a Lawyer.

pleading at the table of sacred love, represented as a judge.

From Penn State Univesity Library

I hereby publicly declare that all entries on this weblog, The Laughing Bone, are the sole creation of the fiery mind of Scot Casey - unless otherwise noted by attribution or quotation - and, that I will make no use of any of the works of Mr. Charles "Bonesy" Jones - beyond those which already exist on this weblog.

That being so awkwardly stated and with no explanatory gloss, allow me to encourage all of you that have any interest in leaving behind some vestige of being, some artifact of soul, after you have shuffled off this mortal coil (Wm. Shakespeare), to gird up your loins, plug your asshole and engage in some dire conference with a lawyer to prepare a SIMPLE WILL. Be sure to bring plenty of patience and lucre.

Henceforth, all work published under the name Scot Casey on this blog is under a Creative Commons license:

Creativity and innovation rely on a rich heritage of prior intellectual endeavor. We stand on the shoulders of giants by revisiting, reusing, and transforming the ideas and works of our peers and predecessors. Digital communications promise a new explosion of this kind of collaborative creative activity. But at the same time, expanding intellectual property protection leaves fewer and fewer creative works in the "public domain" — the body of creative material unfettered by law and, to quote Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, "free as the air to common use."

Until 1976, creative works were not protected by U.S. copyright law unless their authors took the trouble to publish a copyright notice along with them. Works not affixed with a notice passed into the public domain. Following legislative changes in 1976 and 1988, creative works are now automatically copyrighted. We believe that many people would not choose this "copyright by default" if they had an easy mechanism for turning their work over to the public or exercising some but not all of their legal rights. It is Creative Commons' goal to help create such a mechanism.

Now for a few quotes that have educated, amused and sustained me over the last year or so:

Intestate Succession - From Britannica.com

In the law of inheritance, succession to property that has not been disposed of by a valid last will or testament. Although laws governing intestate succession vary widely in different jurisdictions, they share the common principle that the estate should devolve upon persons standing in some kinship relation with the decedent. Modern laws of intestacy have tended not to emphasize the traditional concern that property be kept within the bloodline through which it came to the decedent. Modern practice also tends to favour the rights of the surviving spouse, whether or not he or she is regarded as kin, and (in most jurisdictions) to ease restrictions on inheritance by illegitimate children.

From The Tragedy of King Richard the Third. Act IV. Scene IV:

Duch.

Why should calamity be full of words?

Q. Eliz.

Windy attorneys to their client woes,

Airy succeeders of intestate joys,

Poor breathing orators of miseries!

Let them have scope: though what they do impart

Help nothing else, yet do they ease the heart.

Duch.

If so, then be not tongue-tied: go with me,

And in the breath of bitter words let’s smother

My damned son, that thy two sweet sons smother’d.

[A trumpet heard.]

The trumpet sounds: be copious in exclaims.

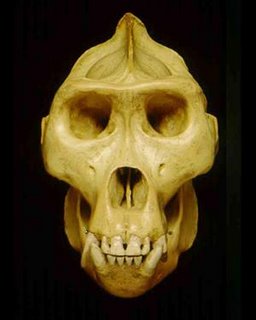

From Human Evolution

From Human EvolutionHamlet.

There's another: why may not that be the skull of a lawyer? Where be his quiddits now, his quillets, his cases, his tenures, and his tricks? why does he suffer this rude knave now to knock him about the sconce with a dirty shovel, and will not tell him of his action of battery? Hum! This fellow might be in's time a great buyer of land, with his statutes, his recognizances, his fines, his double vouchers, his recoveries: is this the fine of his fines, and the recovery of his recoveries, to have his fine pate full of fine dirt? will his vouchers vouch him no more of his purchases, and double ones too, than the length and breadth of a pair of indentures? The very conveyances of his lands will hardly lie in this box; and must the inheritor himself have no more, ha?

Horatio.

Not a jot more, my lord.

Hamlet.

Is not parchment made of sheep-skins?

Horatio.

Ay, my lord, and of calf-skins too.

Hamlet.

They are sheep and calves which seek out assurance in that. I will speak to this fellow.- Whose grave's this, sirrah?

Related Discussion from Mauled Again

Courts have long held under principles of public policy, that a decedent cannot direct the destruction of property after death. Thus, even though a person, while alive, can light a proverbial cigar with a proverbial rolled up $20 bill, one cannot order one's cash burned after death. Nor, according to several cases, can one order the razing of one's home (even if one could do so during lifetime), and this is an issue aside from permits and environmental concerns.

So in the classic hypothetical, when the decedent dies, love letters written to the decedent are found. Make the hypothetical interesting by identifying the writer as either a famous person or, better yet, someone whose position and status makes those letters scandalous (as if today there's much left that can fall within that term). So, however one wants to set up the facts, do so in a way that gives the love letters value. In our world of Warhol minutes, reality TV, and gossip run amok, it's unlikely that any love letters would lack value. The same is true of any other sort of letter (though love letters makes the hypothetical more interesting and gets the students' interest). The more secrets, the deeper the secrets, the more widespread those impacted or interested in the secrets, the higher the value of the email or other correspondence. I suppose that for celebrities' correspondence, the value reaches a peak and the issue is more likely to be litigated.

So if a decedent cannot order the burning of cash or the razing of a home, should a decedent be permitted to order the destruction of correspondence that has value? If the answer is yes, then those carving out an exception need to define the line, and I'm not convinced that the line can easily be drawn. Would it extend to home movies? Audiotapes? Photographs? Art work?

Surely one can think of reasons that the decedent would want the material destroyed, but then again, the decedent could have destroyed the material while alive. Except that destroying email on the email server of a commercial internet provider isn't easily accomplished, and might not be possible with emails less than 30 or 60 or 90 days old. But one also can think of reasons OTHER people would want the decedent's email and other materials destroyed: as one person pointed out (archived at Politech), "the emails might reveal the secret abortion of the sister or the secret first marriage of the father."

Digital technology puts yet another wrinkle on the issue. Paper correspondence sent to another person is in that other person's hands, and unless a photocopy was retained, it is beyond the reach of the decedent. The decedent cannot destroy it. Nor do the decedent's executor and beneficiaries have access (though, of course, the recipient's executor and beneficiaries might get their hands on it). With email, not only is the incoming correspondence on the server or computer, so too is the outgoing correspondence, or at least some of it is. Keep in mind that email is far more voluminous than is paper correspondence, perhaps by an order of magnitude.

Putting a direction in a will to destroy "love letters" could be counterproductive because wills aren't private. They become public when probated. "Destroy the love letters ....." or "Burn the letters received from ...." language would create all sorts of an uproar, and even if the contents never became public, the existence of the material would fuel the rumor mill for a long time, even if the decedent was not a national or international celebrity. After all, each one of us is a celebrity in our own little world. And, of course, "burn all correspondence" is overkill that by reaching legitimately retained financial and other information necessary for tax return and other compliance would give a court even more reason to hold to the principle that one cannot order the destruction of property after death.

It makes more sense to direct all property to a pre-existing trust and to give direction to the trustee (assuming, of course, that there is a right to order destruction of property). If the will inadvertently or deliberately incorporates the trust by reference, all bets are off because the trust is part of the probated will rather than a separate entity.

Tuesday, January 03, 2006

Notes On Difficulty

For those of you looking for pure B. Jones, you will have to forgive this bit of autobiography below. However, the revelation into Jones' personality provided by Steiner's essay was so profound for me that I thought it merited posting here.

To say that this last year has been difficult would be something of an understatement. In the retrospect that comes with the turning of the year, it seems the word difficult has been in my mouth more often than any other. And so it was with no fear of irony that I pulled George Steiner's On Difficulty and Other Essays from B. Jones' 'bookcase of the essentials' the other day. He had often referred me to the central essay, saying that it was a key to unlocking the dungeon of the twentieth century (or something like that).

Of course, as with so many essays, poems, books, songs, etc. that he constantly implored me to read, I had never read it. Turning now to the central essay and scanning the paragraphs, I came across this remarkable passage:

He will labour to undermine, through distortion, through hyperbolic augment, through elision and displacement, the banal and constricting determinations of ordinary, public syntax. The effects which he aims at can vary widely: they extend from the subtlest of momentary shocks, that unsettling of expectation which comes with a conceit in Metaphysical verse, to the bewildering obscurity of Mallarme and the modernists. The underlying manoeuvre is one of rallentando. We are not meant to understand easily and quickly. Immediate purchase is denied us. The text yields its force and singularity of being only gradually. In certain fascinating cases, our understanding, however strenuously won, is to remain provisional. There is to be an undecidability at the heart, at what Coleridge called the inner penetralium of the poem (there is a concrete sense in which the great allegories of ingress, of pilgrimage to the centre, such as the Roman de la rose and the Commedia, compel the reader to re-enact, in the stages of his reading, the adventure of gradual unfolding told by the poet).

And if that wasn't a perfect description of the life of B. Jones, then I didn't know what was. I even looked up the publication date (1978) to see if he hadn't come across it in his youth and decided to take it as a credo for living. Simply amazing. I truly regretted that I hadn't read it when he was alive so that I could've discussed it with him. As it was, I stopped everything that I was doing and sat down to read the entire essay.

Essentially, Steiner breaks difficulty into four types: contingent, modal, tactical and ontological. (Now, hang on for a second). His primary focus is with poetry: why certain poems are so difficult to understand. But as I indicated above, what was most fascinating to me was the application of the types to the more elusive difficulties of a life. It was one of those reading experiences where you begin to smile with understanding and then end up laughing out loud at how each new paragraph unfolds. It was like a clockwork play, a perfect sonnet, a shimmering fugue quartet. I have read a fair amount of George Steiner but this was a virtuoso perfomance. In fact, it would be the first thing I would refer people to if they were unfamiliar with Steiner's work. (That Jones pushed Real Presences into my hands before this bewilders me.) So I recommend it. Highly.

I wish I could just post the entire essay here but I don't feel right about that. But here are the four types with passages from Steiner. The concern is poetry but turn them outwards, maybe to something or one that isn't necessarily a poem but is poetic - difficultly so - and see how appropriately they might apply.

Contingent Difficulties - Mostly things that have to be 'looked up'. Words that you don't know. Obscure references. Lexical issues. Answered with a dictionary, concordance, encyclopedia, etc..

In practice, the homework of elucidation may be unending. No individual talent or life-span, no collective industry, can complete the task. But not in theory, not formally. This is my point. Theoretically, there is somewhere a lexicon, a concordance, a manual of stars, a florilegium, a pandect of medicine, which will resolve the difficulty. In the 'infinite library' (Borges's 'Library that is the Universe') the necessary reference can be found. Walter Benjamin suggests that there are cruces and talismanic deeps in poetry which cannot be elucidated now or at all times; they were understood formerly, they may be rightly glossed 'tomorrow'. No matter: in some time, at some place, the difficulty can be resolved.

Modal Difficulties - Takes more than looking up. A fundamental oddness, strangeness that you just don't get. Something like 'culture shock'. I am reminded of when I first read Joyce's Ulysses. I was young and just couldn't figure out what it was about. Of course, now it all seems so obvious that I wonder why I couldn't see it then.

[W]e may find ourselves saying 'this is a difficult poem' or 'I find it difficult to grasp, to place this poem' (the shift into a first-person register of experience is, here, significant) even where the lexicalgrammatical components are pellucid. We have looked up what there is to look up, we have confidently parsed the elements of phrase - and still there is opaqueness. In some way, the centre, the rationale of the poem's being, holds against us.

Tactical Difficulties - Obscurities. Deliberately occult. Codes. Hidden allegories. Puzzles.

The poet may choose to be obscure in order to achieve certain specific stylistic effects. He may find himself compelled towards obliquity and cloture by political circumstances: there is a very long history of Aesopian language, of 'encoding' and allegoric indirection in poetry written under pressure of totalitarian censorship (oppression, says Borges, is the mother of metaphor). The constraints may be of a purely personal nature. The lover will conceal the identity of the beloved or the true condition of his passion.This was all well and good. But Steiner opened up another aspect to me with the following passage:

It is the poet's aim to charge with supreme intensity and genuineness of feeling a body of language, to 'make new' his text in the most durable sense of illuminative, penetrative insight. But the language at his disposal is, by definition, general, common in use. Its similes are stock, its metaphors worn down to cliches. How can this soiled organon serve the most individual and innovative of needs? There have, throughout literary history, been logical terrorists who have taken the implicit paradox to its stark conclusion. The authentic poet cannot make do with the infinitely shop-worn inventory of speech, with the necessarily devalued or counterfeit currency of the every-day.

Just these phrases alone are enough to make me smile: "soiled organon", "logical terrorists", "shop-worn inventory of speech", "counterfeit currency of the every-day". Beautiful.

It was under this type of tactical difficulty that I came across the passage I initially quoted above.

Ontological Difficulties - Essential questions. The very existence, being, of the thing is in question here. Why was it created? Who is the audience? Why is there performance at all? I think of a spectrum from an autistic savant filling page after page with unreadable language to serial murderers 'decorating' their dungeons to Holy Men chanting mantras in isolated caves.

Because this type of difficulty implicates the functions of language and of the poem as a communicative performance, because it puts in question the existential suppositions that lie behind poetry as we have known it, I propose to call it ontological. Difficulties of this category cannot be looked up; they cannot be resolved by genuine readjustment or artifice of sensibility; they are not an intentional technique of retardation and creative uncertainty (though these may be their immediate effect). Ontological difficulties confront us with blank questions about the nature of human speech, about the status of significance, about the necessity and purpose of the construct which we have, with more or less rough and ready consensus, come to perceive as a poem.

This is certainly the most interesting type of difficulty. Perhaps the most vital to my outwardly formed interpretation. To exploring a life lived and died as a poem of sorts. I realize now that the difficulties that I have had in coming to terms with the death of B. Jones are mostly of the ontological type. His life was/is like a poem to me. And I guess the crux of the difficulty is in that tense change marked by /. Because I don't/didn't want the poem to ever end.

I will leave with two passages from Steiner as he says it so much better than me.

It is not so much the poet who speaks, but language itself: die Sprache spricht. The authentic, immensely rare, poem is one in which 'the Being of language' finds unimpeded lodging, in which the poet is not a persona, a subjectivity 'ruling over language', but an 'openness to', a supreme listener to, the genius of speech. The result of such openness is not so much a text, but an 'act', an eventuation of Being and literal 'coming into Being'. [...]

We bear witness to its precarious possibility of existence in an 'open' space of collisions, of momentary fusions between word and referent. The operative metaphor may be that crucial to Mallarme's famous L'absente de tous bouquets, to the modem physicist's determination of 'the unperceived event' in the cloud-chamber, and to Heidegger's equivocation on the 'absence in presence' (the play on Ab- and Anwesen). ln each case the observable phenomenon - the text - is the inevitable betrayal, in both senses of the term, of an invisible logic.